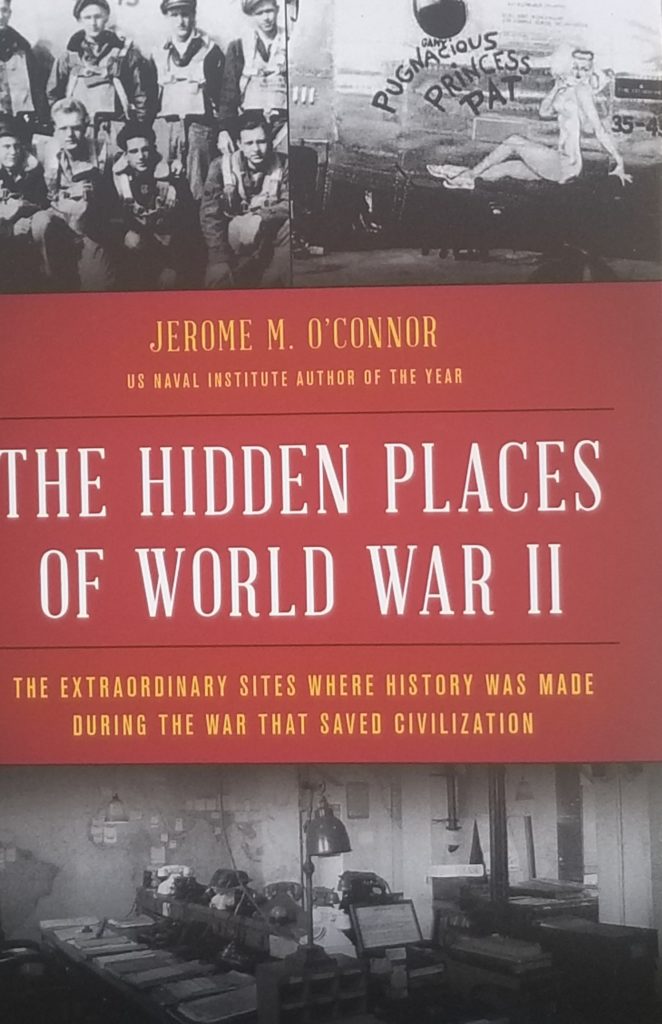

THANK YOU READERS AND Lyons Press FOR MAKING POSSIBLE THE PAPERBACK VERSION NOW AT SELECTED BOOK OUTLETS AND ON AMAZON

Each of 22-chapters examines overlooked aspects of the war. At 87,000 words and 355 pages, the work results from decades of investigation and includes never seen author photos comparing the appearance of the same locales from then to now.

(FOLLOWING IS AN EXCERPT FROM CHAPTER 11 – LAUNCHING THE INVASION – SOUTHWICK HOUSE AND D-DAY)

“HISTORY DOES NOT LONG ENTRUST THE CARE OF FREEDOM TO THE WEAK OR THE TIMID” (Dwight D. Eisenhower)

0500 SUNDAY 4 JUNE 1944 DELAY AND DISAPPOINTMENT

Shortly after a 415am weather briefing on June 4, General Eisenhower stepped-out for another smoke under the portico with the eight Doric columns of the immense 1841 three-story mansion near Portsmouth on England’s southeast coast. Into the first of up to four daily packs of Camels and fifteen cups of coffee, before dawn he and his subordinate commanders had already completed the first of two daily weather briefings with British meteorologist, Group Captain J. M. Stagg. Within the elegant interior, Stagg and his staff had just recommended a delay to the start of Operation Overlord, the liberation of the European continent from Nazi oppression. Ike had immediate major decisions to make.

Throughout the mansion’s spacious gardens were scattered numerous half-cylindered corrugated steel structures named after their inventor, Peter Nissen. Tents of various sizes and temporary housing extended from the surrounding woods almost to the mansion’s entry. For a brief time the ancestral home of the Thistlewaite family, Operation Overlord’s pre-assault naval communication center, would be the most important place on earth.

From where the stately home resided in the low hills above Portsmouth Harbor, Ike could almost see the water and part of the vast armada containing every type of naval vessel afloat. In addition to Portsmouth, eleven other British ports were equally laden with so many ships that it was almost possible to walk with dry feet from one vessel to the other, so closely were they moored. The supreme commander of history’s mightiest invasion force knew that every man from general and admiral to mechanic and rifleman, all 156,000 of them and millions more behind, awaited his command to instantly move from camps to landing vessels, or from the ships to the beaches. But it wouldn’t come that day and it wouldn’t come the next.

From where the stately home resided in the low hills above Portsmouth Harbor, Ike could almost see the water and part of the vast armada containing every type of naval vessel afloat. In addition to Portsmouth, eleven other British ports were equally laden with so many ships that it was almost possible to walk with dry feet from one vessel to the other, so closely were they moored. The supreme commander of history’s mightiest invasion force knew that every man from general and admiral to mechanic and rifleman, all 156,000 of them and millions more behind, awaited his command to instantly move from camps to landing vessels, or from the ships to the beaches. But it wouldn’t come that day and it wouldn’t come the next.

The first met report that June 4 – the second weather update would be at 645pm – painted a discouraging picture of high winds, low clouds, and reduced visibility predicted for June 5, the date of the invasion. Any one of the expected weather disturbances would hinder accurate naval gunfire and make certain the swamping of LCVP landing craft – the Higgins Boats – at the moment of dropping their bow ramps on the beach, if they even made it that far. Without fair visibility, erroneously dropping 300 paratroopers from the 101st Airborne Pathfinder teams, could fatally divert the 23,000 jumpers in the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions to follow. Any expectation of air cover over the beaches on June 5, Ike had been bluntly told, would be “impossible.” The ceiling would be under 1,000 feet. Yet, on June 4 major elements of the naval forces were already at sea, and, as Churchill would later write, “the movement was as impossible to stop as an avalanche.”

…As Eisenhower asked around the room for opinions, General Bernard Montgomery told Ike of his keenness to go, but none of the others were as hopeful. Each had a reasoned objection to explain why his part of the invasion force faced operational hurdles if not defeat. On that June 4, 1944 pre-dawn, weather made the decision: the invasion planned for June 5 stood-down as a no go. While a disappointment, it was not yet a setback. At least two, perhaps three days remained within the window of ideal low tide and bright lunar conditions needed to launch the invasion. But if the elements continued sour, the next time the moon and tides aligned wouldn’t come until June 19.

Waiting another two weeks came with the potential of defeat at the water’s edge. Keeping men already at sea or fenced-in at temporary camps another fortnight risked discovery and a loss of the vital edge needed for soldiers approaching sudden combat. Fresh troops rotating into the camps expected to be vacated by the invading soldiers would have nowhere to go. Miles of pre-positioned equipment on roads and at supply depots throughout England would need to be re-situated, presenting a logistical muddle on the narrow roads.

Waiting another two weeks came with the potential of defeat at the water’s edge. Keeping men already at sea or fenced-in at temporary camps another fortnight risked discovery and a loss of the vital edge needed for soldiers approaching sudden combat. Fresh troops rotating into the camps expected to be vacated by the invading soldiers would have nowhere to go. Miles of pre-positioned equipment on roads and at supply depots throughout England would need to be re-situated, presenting a logistical muddle on the narrow roads.

Some of the 6,939 vessels of all types, including 59 convoys stretching over 100 miles, would need re-fueling or re-positioning. By then, German spies or overhead reconnaissance might have concluded from the evidence of masses of troops at scores or camps, and lurking ships in all the harbors, that the invasion wouldn’t happen at the Pas de Calais as expected. Maybe, the German high command could have concluded, maybe the invasion would begin at an obscure location not as well fortified. Maybe it would begin in Normandy.

With the storm lashing the mansion, Ike returns to Southwick House in the pre-dawn hours of June 5 to make the most consequential decision of the 20th century.