SECRET SERVICES

Liverpool’s Western Approaches Command Center,the unknown link with the Battle of the Atlantic,may be World War Two’s last remaining major secret.

By Jerome M. O’Connor

MEMBER: American Society of Journalists and Authors

Discovering the legendary underground fortress that once controlled Britain’s part in the Battle of the Atlantic seemed unlikely. British tourist offices in New York and London and several war museums could not verify the existence of the 100 room, 50,000 sq. ft. underground enclave. A local man had a discouraging opinion: “It was open but they locked it and threw away the key.” Did the intelligence headquarters that so powerfully contributed to Britain’s wartime salvation exist only in memory or did it languish ignored and unheralded?

HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT

PROLOGUE

Nearly seven decades after history’s greatest war, few historical accounts acknowledge or even refer to the war-winning accomplishments that took place in a massive Liverpool citadel known as the Western Approaches Command Center (WAC). The underground complex served as command and control headquarters for the entire British effort in the Battle of the Atlantic, World War Two’s longest fight.

The accepted wisdom held that WAC – if it even existed – had been demolished. It was believed that control of convoys, warship operations, enemy aircraft interception and U-boat pursuits, originated in the Old Admiralty Building near the Mall in Whitehall. In fact, the combined forces command center near the battered Liverpool docks functioned separately, and its innovations were decisive in defeating the Atlantic U-boats.

Winston Churchill, a frequent visitor, said nothing about the citadel in his six-volume history of the war. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, who reviewed D-Day plans in the building’s lowest depths, never referred to the top-secret enclave in his own war history, Crusade in Europe. Until now, nothing has ever been published about WAC and its vital actions and processes.

The museum is so little known that many Liverpool residents are unaware that the seventy foot deep jumble of rooms are open to view, and that visitors can walk the same Byzantine complex restored with its original furnishings and equipment. The fortress is so extensive that even the museum’s management is unaware of its full dimensions. “There could be 150 rooms but I have never seen it all myself.”

LIFELINE OF THE ATLANTIC

In mid-June 1941, a 57ship convoy sailed for Liverpool from Halifax and Sydney, Nova Scotia, and Bermuda. Although designated as HX, a “fast convoy,” the merchant ships averaged a lethargic 7.7 knots, about the pace of a casual jogger. Their holds contained mixed cargos of steel, iron ore, trucks, bombs, nitrates, oil, grain, and manufactured flour. With England short of everything then, the Royal Canadian Navy escort could muster only five 950- ton, 16 knot Flower Class corvettes and the HMS Laconia, converted from a slow Cunard passenger liner into a sluggish armored cruiser. Eighteen days later only 45 ships trailed into Liverpool’s North and Birkenhead docks. The convoy had been decimated by a ten U-boat wolf pack that sunk or heavily damaging eight ships. Yet, HX-133 was one of the more fortunate convoys in that bleak year.

Liverpool’s seven-miles of docks, the second largest after London, disembarked most of the cargo and troop convoys destined for Continent, and almost the entire American produced tanker oil. Without oil England’s defeat loomed.

Apart from London, the much smaller cathedral city of Liverpool suffered the most wartime damage. Repeated bombings had devastated its center and most of the docks. But cutting the convoy lifeline from America to England was not the only reason why Hitler had given the Luftwaffe standing orders to destroy the city. Through signals intercepts and spies, German intelligence had concluded that Britain’s principle command and control center lay near Liverpool’s waterfront. Finding and destroying it by bombing or invasion could win the war for Germany.

ENTERING THE “DUNGEON”

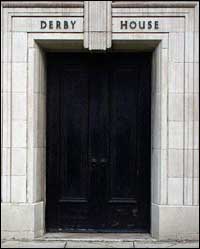

Near the original gilded Cunard headquarters and only steps from the 1754 Town Hall, Derby House, a 1930’s white slate office building hid in plain sight while serving as WAC headquarter from February 1941 until the war’s end. Commodores and captains from most of Liverpool’s 1,285 war convoys entered the same black double-doors as do today’s trickle of visitors.

After identity cards were examined from a desk at the first level “reception room,” wartime visitors pushed aside gas-blocking mesh curtains to descend into the concrete encased bubble. The citadel expanded and extended so widely that modern visitors view blank walls blocking one-time entrances into other rooms that led under the street and into adjacent buildings.

Housed in nearby dormitories or in rented rooms within walking distance, each eight to twelve hour watch included a support staff of up to 600 Royal Navy and Royal Air Force enlisted women and officers. The GPO (General Post Office) had separate responsibility for another layer of civilian technicians and operators. All were sworn under the official Secrets Act, which, if violated, meant life in prison. Many who affirmed the act’s requirements have yet to disclose their wartime activities.

The enlisted staff, supervising officers, and a succession of convoy commanders swirled within a turbulence of tightly organized and highly audible action and activity. Telegraph sets clattered, scores of teletype machines thumped, as hundreds of telephones with their characteristic ‘ring ring‘ sounds competed with the clangor of teletype bells that increased in number according to the incoming message’s importance. Spartan working conditions were further aggravated by thick humidity, weak illumination, a cigarette and cigar haze, and the need for immediate implementation of constant changes to operational orders. Often unable to leave because of incessant air raids above, the self-described “cave dwellers” were given a reprieve with the installation of sun lamps, a staff mess, emergency sleeping quarters, and modest recreational facilities.

WHERE THE AMERICAN WAR STRATEGY BEGAN

In mid March 1941, immediately after passage of the Lend-Lease Act, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered his US Navy Chief of Staff, Captain Louis E. Denfeld, to meet with then Commander-in Chief-Western Approaches, Admiral Sir Percy Noble. Held in the newly opened WAC, two nights of the conference were disrupted by intense air attacks on the nearby docks, but the concrete box had been built to contain even direct hits. The talks ended by endorsing FDR’s “all aid short of war” directive, affirming that the “center of gravity” for the European theatre depended on first defeating the U-boat threat. From these meetings evolved the epic Roosevelt/Churchill doctrine governing the historic strategy of the entire war- victory in Europe came first.

After America officially entered the war, the WAC entry desk began issuing passes to commanding officers of US Navy destroyer and destroyer escort divisions, submarine squadrons, and troop transports. Although 80% of Liverpool’s docks were destroyed, they would embark 2.1 million GI’s in the invasion of the continent.

THE HEART OF THE MATTER – COMBINED OPERATIONS CONTROL

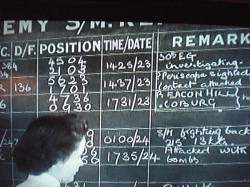

Occupying an out-sized area in the bunker’s lowest level (above), a synchronized intelligence and operations center processed messages containing reports of U-boat positions, Allied convoy movements, coastal airfield operations, and the docking of individual ships. Even plausible rumors had a place. The assembled details became part of constantly updated three-dimensional display tables, or went on a giant grid map occupying the entire rear wall.

In the unremitting U-boat hunt WAC radio operators received sighting reports from ships, listening stations, and aircraft. After America’s entry, reports entered the complex from US Navy destroyers, submarines, and PBY Catalina flying boats. After positive identification, teletype operators sent coordinates to the nearest RAF coastal airfield to scramble attack aircraft.

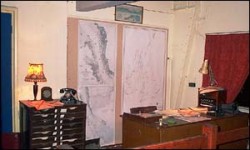

As part of a multi-task checklist, Allied ships were warned to avoid U-boat infested areas, while, in London at the Admiralty, the Submarine Tracking Room and the Air Ministry sent their intelligence to WAC by encrypted teletype, coded radio messages, or over a telephone hot line. Messengers then hand-delivered, telephoned, or called voice reports through brass speaker tubes leading to the Central Operations Map room. Summaries and intentions from London and everywhere quickly made their way to the Chart Room, the nerve center and the principle reason for the existence of the Western Approaches Command Center.

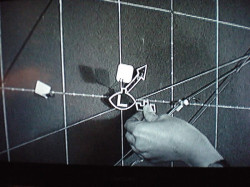

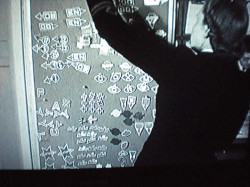

From tables holding relief maps, naval enlisted WREN’ s with wooden push-rods moved color-coded symbols of U-boats known to be located between the Orkney Islands at the tip of Northern England to the southern Scilly Isles, or beyond Ireland into the near Atlantic. Enemy positions and the deployment of Allied resources were displayed on the room-dominating seventy by twenty-two foot high lack painted fibre board plot (above).

To exactly situate a report, a WREN balanced on a telescoping ladder to reach a grid coordinate. A convoy’s course would be indicated by twisting color-coded elastic string around push pins, or the string would be extended to more pins along the grid. Additional colored filaments followed the track of an inbound enemy bomber attack, or plotted the last known position of a U-boat or wolf pack. WRENS also used the pins to attach folded papers to target areas to represent ships, aircraft, or U-boats. The map continued into another major section of the Operations room, itself stacked with clipboards and continually re-chalked blackboards. During peak periods in the Battle of Britain, the map unfolded a perversely festive sea of paper and varicolored elastic.

In a communications challenged era, the corded switchboards, teletype machines, radios, and scores of color-coded telephones, were coordinated into one central communications chain, facilitating links throughout the entire outside command structure. The network connected WAC with 10 Downing Street, the Admiralty, Cabinet War Rooms, Bletchley Park, General Eisenhower’s headquarters, coastal airfields and radar stations, ships at sea, and other strategic locations.

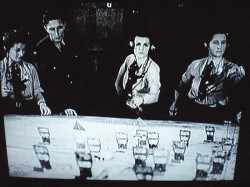

PLAYING GAMES IN THE WAR ROOMS

On large tables and on floors (R) in two separate rooms, one in the WAC and the other occupying the entire top floor of the adjacent Exchange Buildings, one of the earliest ASW simulators set two teams totaling 24 players against each other. Moving varicolored paper symbols across a chart of the North Atlantic, one team represented commanders of Allied convoys and their naval escorts, as well as aircraft and warships at their disposal. The opposing side portrayed U-boat commanders and their likely counter – tactics. A stand-in gamer represented Vice-Admiral Karl Doenitz, Commander-in-Chief U-boats (BdU), at his own concrete headquarters in Lorient, France. Over 5,000 Allied officers attended the six day training course. Those who failed a simulation were politely handed a printed card by a smiling WREN officer: “Your ship has just been sunk. You have no further part in this exercise.”

Churchill’s status merited its own communication process. During regular visits he made and received calls from a red telephone in a booth (L) – the only one in WAC – that linked to a secure outside line. The telephone connected directly to Churchill’s own underground headquarters in the Cabinet War Rooms near 10 Downing Street in London. When Churchill used the booth, a lone Royal Marine stood sentinel outside.

Churchill’s status merited its own communication process. During regular visits he made and received calls from a red telephone in a booth (L) – the only one in WAC – that linked to a secure outside line. The telephone connected directly to Churchill’s own underground headquarters in the Cabinet War Rooms near 10 Downing Street in London. When Churchill used the booth, a lone Royal Marine stood sentinel outside.

Another closely guarded compartment had a single teletype machine and one operator with only one duty – wait for “flash priority” messages from Bletchley Park. Code-named, ‘Station X,’ Bletchley’s electronic computer, “Colossus” – considered to be the world’s first – had revealed the riddle of the Nazi Enigma cipher machine. The ULTRA secret, second only to the Manhattan Project in secrecy, meant that Enigma generated orders to Atlantic wolf-packs were often plotted on the Chart Room tables and wall map even before U-boat captains could change course.

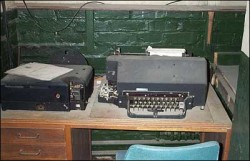

Encrypted signals on WAC’s ULTRA teletype were printed on narrow, spooled, punched paper strips, decoded, and then handed through a tiny window to a messenger in the main teletype room for delivery to a duty officer. The teletype room still has ten of the slow speed machines, memorable for their recurring “chunk chunk” sound. Originally developed by the Teletype Corporation of Skokie, Illinois, the Model 15 machines were an essential communications link throughout the war.

“I HOPE THAT YOU WILL ARRANGE YOUR ROUTINE TO SUIT”

Each WAC function connected with the precision of trains entering a major rail station, their actions synchronized as precisely as Big Ben striking the hour. Yet, as an oddity in an otherwise systematic process, then Commander-in-Chief Western Approaches, Admiral Max Horton, 60, (below)) was also the quirkiest. From a staffers war diary: “He had some maddening habits. He played golf all afternoon, then returned (to WAC), played a rubber or two of bridge, and came down to his office and started sending for his staff.“

As with Churchill, Admiral Horton functioned best at night – late night – usually appearing without notice in his large windowed office overlooking the giant map in the Operations Room below. The admiral irritated easily, gray water constantly breaching his bow, and, according to the staffer, “suddenly appearing in worn and split pajamas hair hirsute fore and aft.” To ensure no staff misapprehension as to the intertwining of his

leisure with duty hours, the admiral issued a curt memo: “My routine is golf every day from two to six, and I usually finish my work at 1.0am. I

hope you will arrange your routine to suit.” The agreeable staff afforded the salty admiral abundant sea room, knowing that his war-fighting abilities far exceeded his eccentric behavior. Admiral Horton, a World War One submariner, had the rare ability to discern wolf pack strategy.

America and England ended 1942 unable to improve convoy protection tactics necessary to turn the war at sea in favor of the Allies. Victory in the Battle of the Atlantic swayed in the balance until spring 1943, as U-boats continued to operate unopposed from impregnable bunker bases in Western France (below, wartime and current). After the war, Churchill confided that the U-boat menace was his only abiding fear.

But Admiral Horton transformed the failed doctrine through radical changes in the use of convoy escorts. Rather than relying on a perimeter escort defense, separate support warships were added inside convoys, each with independent orders to hunt and destroy U-boats. Almost immediately, the tide turned. Within six months of assuming WAC command, the north Atlantic U-boat threat had ended. By mid 1944 not one North Atlantic cargo ship had been lost to U-boats.

(AFTER HUNDREDS OF ATTEMPTS NO U-BOAT BASE IN FRANCE WAS EVER DESTROYED OR EVEN SEVERELY DAMAGED)

By war’s end WAC had become a gigantic enterprise, enormously expanding beyond its beginnings at Derby House. On D-Day it had responsibility for thirty seaborne support groups, most with one or more escort carriers. The original staff had expanded into a medium-sized city of 121,500 officers and enlisted staff, with another 18,000 Wrens operating from dozens of separate buildings or bases.

In appreciation for his leadership and command abilities, Admiral Max Horton received the Legion of Merit from General of the Army, George C. Marshall. By securing North American supply lines across the Atlantic, Western Approaches Command enabled the US Navy to utilize maximum force in the Pacific campaign. The invasion of Europe won the European war, but defeating the U-boats prevented its loss.

VISITING THE CITADEL

Traveling from London on the many trains to Liverpool is the easy part. Actually entering the museum can be challenging. No advance reservations are accepted and there are no guided tours. No museum in Liverpool, London, Visit Britain, the US Naval Institute, the Imperial War Museum and British National Archives, or anywhere has substantive knowledge of WAC’s existence, availability, and its history changing war secret. The author was repeatedly informed by the Liverpool Merseyside Tourist Authority not to visit as no contact with management was possible. The site is so poorly attended that admissions are restricted from only April 1 to October 31, with an admission fee equivalent to $9.00 per person. On the day of the author’s visit, however, only 18 were in the museum in five hours, of which 12 were children with parents. It was a free day from school. Yet, overcoming the restrictions and oddities of access will satisfy all expectations by revealing what is likely the last major secret of World War Two.

Chicago historian and journalist, Jerome M. O’Connor, received the 2000 US Naval Institute Author of the Year award. His articles have appeared in numerous magazines and newspapers. This work results from comprehensive investigation and a lengthy visit to the Western Approaches Command Center. It is one in a continuing series of features revealing the unknown or overlooked people, places, and significant events of the 20th Century, World War Two being its defining event. In addition to the above color images by author, a detailed photo gallery containing rare and never published images is being periodically added to this page.

PHOTO GALLERY – RETURN FOR REGULAR ADDITIONS FROM AUTHOR’S INSPECTION AND COLLECTION