For many of the fifty million plus annual visitors to Chicago,the city’s origin could be assumed as being at Michigan Avenue and Wacker Drive. It’s understandable; diagonal bronze lines in the pavement show that Fort Dearborn stood at that very location. It could thus be concluded that the city to-be began from there,but it didn’t. The fort was established in 1803 to be a sentinel against encroachment by foreign powers into the interior from the Chicago River. The I&M Canal, the waterway that connected the Atlantic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico thru Chicago, wouldn’t begin construction until 1836 – thirty-three years later. It started from the Bridgeport neighborhood, about 5 miles from downtown Chicago. When it was finished in 1846 the canal would intersect a portage traveled by Marquette and Joliet in 1673, and that 173 years later would connect Chicago via the Des Plaines and Illinois rivers to the Mississippi and the Gulf of Mexico. Thus, Chicago was born with the building of the I & M Canal, and for decades it would be the fastest growing city in the world.

For many of the fifty million plus annual visitors to Chicago,the city’s origin could be assumed as being at Michigan Avenue and Wacker Drive. It’s understandable; diagonal bronze lines in the pavement show that Fort Dearborn stood at that very location. It could thus be concluded that the city to-be began from there,but it didn’t. The fort was established in 1803 to be a sentinel against encroachment by foreign powers into the interior from the Chicago River. The I&M Canal, the waterway that connected the Atlantic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico thru Chicago, wouldn’t begin construction until 1836 – thirty-three years later. It started from the Bridgeport neighborhood, about 5 miles from downtown Chicago. When it was finished in 1846 the canal would intersect a portage traveled by Marquette and Joliet in 1673, and that 173 years later would connect Chicago via the Des Plaines and Illinois rivers to the Mississippi and the Gulf of Mexico. Thus, Chicago was born with the building of the I & M Canal, and for decades it would be the fastest growing city in the world.

Although the North American continent had been partially explored and settled by French, English and Spanish explorers and settlers, until Marquette & Joliet’s Voyage of Discovery no one had explored the great river the Indians called ‘Missipi’ from the Great Lakes.

Finding the “father of waters” would establish the long sought connection from the Atlantic to the Gulf of Mexico through the Great Lakes. Starting from present-day Green Bay WI, the two explorers voyaged the Fox and Wisconsin rivers to Prairie du Chien, and were then carried downstream on the Mississippi to the mouth of the Arkansas River. On the return journey, anxious to report their findings to the governor of New France at Quebec, they were told of an easier way back to Lake Michigan by paddling along the Illinois and DesPlaines rivers (see map), encountering only a two-mile portage, over which they carried the canoes. (En-route, they also discovered a mini continental divide where the waters of the Des Plaines and Illinois rivers flowed back to the Mississippi.)

They then entered the Chicago River, passing along its south branch to the river’s single leg at Wolf Point, and along what is now downtown Chicago to nearby Lake Michigan and back to Quebec. Although the voyage of over 2,500 miles was a major success, it would take another 163 years for the Illinois and Michigan Canal to make the connection that would also create a dynamic city from a frontier town. Marquette returned to the Chicago area in 1674 to winter in the bleakness of a region so desolate even the Indians avoided it, thus becoming the first European to reside in Chicago. When the I&M Canal began construction in 1836, mostly built by Irish immigrant laborers, Chicago had a population of 400. Fifty years later it would be over 1 million with Chicago now connected by water – the most economical and fastest means of travel – with the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico and all that lay beyond. With the opening of the canal, grains, corn, soybeans, lumber and agriculture would flow westward from Chicago, while sugar, molasses, salt, tobacco and oranges would travel from the south. In 1854, Chicago received an additional boost from the start of the railroad era, soon to establish the rapidly expanding city as America’s rail center. As shown in the images below, Bridgeport, where it all began, transitioned from Irish to Polish to Hispanic and Asian, while maintaining its blue-collar roots. Bubbly Creek (the West Fork of the South Branch of the Chicago River, a few hundred feet from where the canal began,) forms the west boundary of today’s Bridgeport, about 5 miles from downtown Chicago.

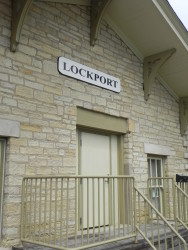

The first of what would become 15 lift locks became the reason for starting a new town 35 miles from the canal’s Chicago origins, and appropriately named after the lock itself, Lockport, IL. Calling itself with some justification,  “the town that made Chicago famous,” Lockport thrived on the now rapidly developing canal traffic that had 288 boats

“the town that made Chicago famous,” Lockport thrived on the now rapidly developing canal traffic that had 288 boats  by 1864, and would move one million tons

by 1864, and would move one million tons  of cargo in 1882, its

of cargo in 1882, its  busiest year. The 1837 (L) Gaylord Building, an imposing structure that many believe was the canal administration headquarters, actually served mostly as a warehouse for parts and materials used in constructing the canal, but has survived to the present day as an example of what a young country could accomplish, even though most of the country’s interior had yet to be explored or made a part of the United States. Extending 96 miles from Chicago, where it joined the Illinois River at La Salle and continued to the Mississippi, the I & M Canal also had 5 aqueducts and 4 hydraulic power basins, many of which can be viewed today.

busiest year. The 1837 (L) Gaylord Building, an imposing structure that many believe was the canal administration headquarters, actually served mostly as a warehouse for parts and materials used in constructing the canal, but has survived to the present day as an example of what a young country could accomplish, even though most of the country’s interior had yet to be explored or made a part of the United States. Extending 96 miles from Chicago, where it joined the Illinois River at La Salle and continued to the Mississippi, the I & M Canal also had 5 aqueducts and 4 hydraulic power basins, many of which can be viewed today. As seen in this early photo and a current

As seen in this early photo and a current  image, the same rings used to tie the canal boats to the Gaylord Building are still in place. But even with the canal now fully paid by tolls and land sales, and with new

image, the same rings used to tie the canal boats to the Gaylord Building are still in place. But even with the canal now fully paid by tolls and land sales, and with new

towns sprouting along its path, its fate had already been sealed by the coming of the railroad just 6 years after the canal had fully opened from Chicago to the Mississippi. Today, as Metra, the once Chicago & Rock Island railroad still operates from the same tracks known as the Heritage Corridor.

towns sprouting along its path, its fate had already been sealed by the coming of the railroad just 6 years after the canal had fully opened from Chicago to the Mississippi. Today, as Metra, the once Chicago & Rock Island railroad still operates from the same tracks known as the Heritage Corridor.

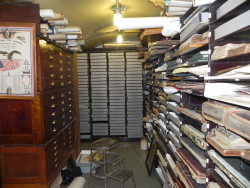

Although rarely visited, a tattered ten-room white-frame building from 1837 served as the  canal headquarters. The mostly uncatalogued clutter of thousands of records, faded legal documents and dusty artifacts, all contribute to the little-known saga of the town and canal that made Chicago famous.

canal headquarters. The mostly uncatalogued clutter of thousands of records, faded legal documents and dusty artifacts, all contribute to the little-known saga of the town and canal that made Chicago famous.