The elegant country house where,on 5 June 1944,General Dwight D. Eisenhower made the historic and risky decision to launch the D Day invasion. After its momentary fame the mansion near Portsmouth – ignored for decades by authors and historians – receded into history. Not quite. We discovered the house as it was on D Day. And now it can be visited with advance application.

The elegant country house where,on 5 June 1944,General Dwight D. Eisenhower made the historic and risky decision to launch the D Day invasion. After its momentary fame the mansion near Portsmouth – ignored for decades by authors and historians – receded into history. Not quite. We discovered the house as it was on D Day. And now it can be visited with advance application.

Urged by coils of lashing winds and rain, on the evening of June 4,1944 General Dwight D. Eisenhower entered Southwick House, a mansion near Portsmouth, England appropriated for the Allied Expeditionary Force advance headquarters.

Urged by coils of lashing winds and rain, on the evening of June 4,1944 General Dwight D. Eisenhower entered Southwick House, a mansion near Portsmouth, England appropriated for the Allied Expeditionary Force advance headquarters.

World War Two had been underway for 1,736 days. The fifty-four year old Supreme Commander had a strategically vital decision to make, its weight a pulsing migraine. Launch Operation Overlord, the greatest invasion in history, or wait for favorable seas. His high command had opposing opinions – half said go and the others said no. And there were competing crises to sort out. A few days before, Air Vice Marshall Trafford Leigh-Mallory argued that dropping Gen. Matthew Ridgeway’s 82nd Airborne Division into the Cotentin peninsula would cause glider losses of 70 percent, and over 50 percent troop casualties. Even worse, top secret Ultra intelligence had detected movement of the German 91st Division into the 82nd Airborne’s drop zone. Wretched weather had already postponed the invasion by a day. A second hold would delay the landings by a fortnight to await more favorable tidal and lunar conditions. Over 5,400 assault craft with 156,000 men were at sea. Three million other soldiers, almost 11,000 aircraft, and a trailing procession of vehicles, equipment, and armament expanded to London and beyond. The option Ike favored would determine the war’s outcome.

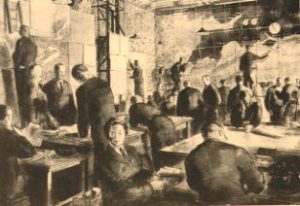

With gale force winds rattling the mansion’s French doors, the Allied high command awaited Eisenhower in the former library over desultory conversation and coffee at a long table or around upholstered chairs. Randomly situated were General Bernard Law Montgomery, Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder, Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsey, Air Vice Marshal Leigh-Mallory, Lt. General Omar Bradley, and Eisenhower’s chief of staff, Major General Walter Bedell Smith, each attended by a staff retinue. All knew that high winds meant high seas and potential disaster for the Normandy landings. And everyone understood that another postponement meant a return to ports and refueling for most of the ships. As an unwelcome irritant a day earlier, Eisenhower had revealed for the first time the invasion’s details to General Charles de Gaulle, then suffered a one-hour lecture on its errors. The Twentieth Century’s most consequential decision and the angst of the French leader in exile, tormented the Supreme Commander with the same persistence as the cascading rain.

Ike went around the room asking opinions. Leigh-Mallory urged a delay until 19 June. Arthur Tedder thought it “chancy.” Ramsey resolutely opposed it. Smith said that it was a gamble but a good gamble. Eisenhower turned to Montgomery: “Do you see any reason for not going Tuesday?” Monty looked Ike squarely in the eye and gave his answer: “I would say go.” At 2145 the Supreme Commander made a preliminary decision: “I am quite positive that the order must be given.” But it could still be rescinded and the ships returned to safe harbor. Final approval would come after Ike fitfully slept for a few hours.

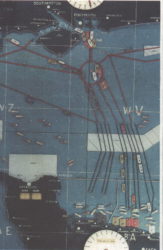

Through churning mud and horizontal rain, at 0330 on 5 June Eisenhower again went to Southwick House in the big Cadillac with his driver, Lt. Kay Summersby. The weather briefing would be decisive. The staff brewed-up steaming coffee. Logs hissed in the fireplace. In the connecting, un-ventilated operations center, the mansion’s former drawing room, hurrying naval WREN’s with clipboards and colored markers wheeled ladders along a massive floor to ceiling plywood

Through churning mud and horizontal rain, at 0330 on 5 June Eisenhower again went to Southwick House in the big Cadillac with his driver, Lt. Kay Summersby. The weather briefing would be decisive. The staff brewed-up steaming coffee. Logs hissed in the fireplace. In the connecting, un-ventilated operations center, the mansion’s former drawing room, hurrying naval WREN’s with clipboards and colored markers wheeled ladders along a massive floor to ceiling plywood

map of the European coastline. Incoming messages constantly revised convoy routing’s toward the invasion beaches. Typewriters and teletypes clattered over background chatter. Telephone wires tangled underfoot. Ike called for meteorologist, Group Captain J. M. Stagg. He had forecast a weather break at the previous meeting, and on this bleak early morning Stagg grinned with confidence. The storm would end by dawn he predicted, and the ships now pressing into the Channel toward France could disembark their men as planned on D-Day.

Ike paced and paced in the now silent room. Minutes passed that seemed like hours. In addition to weather and logistic woes, he knew that holding the men a further two weeks carried the same risks then as now. And by then German intelligence would have detected the build-up and the Normandy location. Ike’s invasion force compared to secretly moving overnight across Lake Michigan the combined populations of Kenosha, Racine and Green Bay, Wisconsin – and with all their vehicles in a heaving storm. The chain-smoking commander stopped, turned to his staff, and quietly but firmly said, “OK. let’s go.”

Within thirty seconds the room emptied, leaving only a drift of blue smoke over the table, a glowing fire reflected on the polished wood floor, and a brooding General Eisenhower sitting alone near the hands of a mantelpiece clock pointing to 945pm. Only fifteen percent of Ike’s invasion force knew combat. Fearing the worst, Eisenhower later penciled a note for the press: “Our landings have failed and I have withdrawn our troops…if any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone.” Across the roiling English Channel, an obscure Normandy beach code-named Omaha impended in the murk. General Irwin Rommel’s seasoned army outnumbered the Allies ten to one. The invasion of Europe was underway, and even Ike couldn’t stop it.

Within thirty seconds the room emptied, leaving only a drift of blue smoke over the table, a glowing fire reflected on the polished wood floor, and a brooding General Eisenhower sitting alone near the hands of a mantelpiece clock pointing to 945pm. Only fifteen percent of Ike’s invasion force knew combat. Fearing the worst, Eisenhower later penciled a note for the press: “Our landings have failed and I have withdrawn our troops…if any blame or fault attaches to the attempt it is mine alone.” Across the roiling English Channel, an obscure Normandy beach code-named Omaha impended in the murk. General Irwin Rommel’s seasoned army outnumbered the Allies ten to one. The invasion of Europe was underway, and even Ike couldn’t stop it.

After the first landings and a flicker of possible success, Eisenhower stepped outside for photos and a quick smoke, and then revisited the operations room. Ten-minute updated reports were being shuttled from ships and the battlefield to the giant, painted map. Made by a Midlands toy firm, it covered the entire European coastline from Norway to Spain. Only the top-secret fifty-mile Operation Overlord section needed fitting after delivery, its installers then detained until after the invasion.

After the first landings and a flicker of possible success, Eisenhower stepped outside for photos and a quick smoke, and then revisited the operations room. Ten-minute updated reports were being shuttled from ships and the battlefield to the giant, painted map. Made by a Midlands toy firm, it covered the entire European coastline from Norway to Spain. Only the top-secret fifty-mile Operation Overlord section needed fitting after delivery, its installers then detained until after the invasion.

Soon after the Normandy landings, Ike left Portsmouth for SHAEF headquarters at Bushy Park outside London, and then to a new forward base in France on August 9. Allied D-DAY casualties of 10,300 included at least 2,500 killed in action. But the transient fame of Southwick House in launching the Normandy invasion became a casualty of a different type. Countless movies, books and histories retelling the invasion saga bypassed the house and Eisenhower’s epic order. Though few are aware of it, Southwick House not only exists now as it was on 6 June 1944, subject to conditions, it may also be visited.

Except for a glare of white paint replacing wartime camouflage, the exterior is little changed from 0830 on 6 June 1944, when Eisenhower stood for photos at the columned front entrance. At that hour on Omaha Beach, ninety miles due east from the entrance, soldiers from the US First Infantry’s 16th and 116th regiments confronted enfilading and plunging fire from a dedicated enemy atop one-hundred foot high bluffs. Sixty years later, the library and drawing room are appointed as they were on D-DAY, And the massive plywood map, set to 0630 hours, D-DAY H-HOUR 6 JUNE 1944, is unchanged from an expectant early morning when General Dwight D. Eisenhower said, “let’s go.”

VISITING SOUTHWICK HOUSE

VISITING SOUTHWICK HOUSE

Trains depart London every thirty minutes for the 90-minute trip to Portsmouth. Buses or taxis connect to the mansion, about five miles from town. NOTE THAT THE PROCEDURE FOR VISITING HAS CHANGED. Southwick House is a military training establishment and visits can confirmed only on Thursday and only by first making arrangements by email at DSPG-HQ-information@MOD.uk.

Portsmouth itself is a living maritime museum, with the 17th Century Historic Dockyard, the hull of Henry VIIIs flagship, Mary Rose, Lord Nelson’s flagship, Victory (on which he died at Trafalgar), the Royal Navy Museum, D-Day Museum, and the same embarkation ports and many buildings used by US and Allied forces preparing for the Normandy invasion. Enhance the D-Day experience from Portsmouth by crossing the English Channel on P&O or Brittany ferries to ports near Sword and Juno beaches. Unopposed landings are expected for modern visitors.