FROM 1903 SCORES OF DAZZLING AUTO SHOWROOMS GAVE THE YOUNG INDUSTRY A GAME CHANGING JUMP-START

THE ONLY PLACE IN CHICAGO TO BUY THE AUTOS THAT TRANSFORMED CHICAGO AND AMERICA

DOZENS OF THE ORIGINAL SOUTH MICHIGAN AVENUE BUILDINGS REMAIN

DESTINED TO BE CHICAGO’S NEXT MAJOR ENTERTAINMENT DISTRICT

BY JEROME M. O’CONNOR, CHICAGO SUNDAY TRIBUNE, OCTOBER 21, 2012

When Henry Ford arrived by train in Chicago’s Central Station in 1905, he was just steps from the South Michigan Avenue site that would be his first store outside Detroit. His new plan to sell automobiles from bright showrooms would change Chicago and America – and transform a quiet city neighborhood into the largest and most glamorous concentration of auto dealerships in the country.

Chicago’s historic Motor Row on South Michigan Avenue is back in the news with developers’ plans to rejuvenate the area as an entertainment and restaurant zone near the McCormick Place convention center. The effort is just the latest attempt to return the area to a semblance of its former glory. In 2001 the city established a Motor Row Landmark District that included 55 buildings in recognition of its importance.

At the turn of the last century, with the battle between the reliable horse and the undependable carriage still in doubt, Ford picked a promising location for his risky business expansion. Close to Prairie Avenue’s new wealth, it was on one of Chicago’s first fully paved streets, flat as a billiard table and ideal for test drives.

While he wasn’t the first on Motor Row – that distinction goes to the Winton Motor Carriage Co. in 1903 – Ford would prove to be the magnet that attracted 116 dealers selling 123 models, including coupes, tonneaus, phaetons and roadsters, behind wide-windowed storefronts with 180-foot-deep bays for easy car access.

THE ONE-TIME FORD AGENCY 2012 AND 1905 COLISEUM & 1st REGIMENT ARMORY CIRCA 1910 – LOCATIONS FOR FIRST CHICAGO AUTO SHOWS

From 12th Street (later renamed Roosevelt Road) to 31st Street and on adjacent Indiana and Wabash avenues, repair garages, accessory dealers and parts suppliers built scores more stores. A frantic rush to buy began and only South Michigan Avenue could fill the need.

Anticipating the historic change, the Studebaker brothers quickly phased out their soon-to-be obsolete carriages and wagons from five floors of showrooms at 410 S. Michigan to sell cars farther south at 2036 S. Michigan.

Chicago’s auto registrations soared from 300 issued in 1900 to 90,000 in 1920 to an astonishing 300,000 in 1925, according to a 2001 landmarks commission report. Horses went to pastures as new bungalows now included garages instead of barns. Starting in 1913 with the Lincoln Highway, numerous national roads were constructed in the following years, including the Dixie Highway in Illinois.

The cars entering Motor Row’s flourishing dealerships had a short stay – in on Monday, showroom on Tuesday, sold on Wednesday. Nationwide, at least 2,800 carmakers sporting marques from Ace and Acme to Zent and Zimmerman, some swapping scythes and buckboards for axles and engines, got on board.

In 1906, John J. Glessner, one of the wealthiest men in the city and a founder of International Harvester, bought a glossy Pierce Arrow Victoria Tonneau from the H. Paulman agency at 1321 S. Michigan, the first of many cars, and modified the coach house of his Prairie Avenue mansion (below circa 1905 and 2012) into a garage.

The Tribune in 1909 was along for the ride, marveling at how far Motor Row had come and pointing out that at least 15 new makes had been added in just the last 18 months. In a special section for the annual Chicago Automobile Show, the Tribune crowed, “Chicago has the most imposing automobile row of any city in the country, and claim for a world’s record wight well be made without much chance of there being any dispute.”

With the Coliseum only steps from Motor Row, the auto show had been gaining traction since 1901. In 1911, it expanded to twice yearly and spilled over into the adjacent First Regiment Armory.

Motor Row pulled out all the stops for that first fall auto show. A seven-column broadside read, “Big Parade Finds ‘Motor Row’ in a Blaze of Electric Radiance,” and reported breathlessly of the “fortune spent in lighting up the street” and how the showrooms would be opened in the evenings for the first time.

Being shown that fall at the Coliseum, self-starters, in use for several years, were becoming standard in more models. “This self-starting idea,” the Tribune said, is certain to make gasoline cars even more popular for it will attract women drivers who hertofore have held aloof vecause of the difficulty of starting a motor, particularly in cold weather.” Another feature becoming standard? Spare tires, or as they were known then, “demountables.”

Increased Tribune display advertising reflected surging interest in the new industry. In October 1911, Stevens-Duryea advertised a limousine with “a four-cylinder power air pump to inflate tires, coat and robe rail, water and toilet bottles, speaking tube, glove tray with mirror, flower case, electric cigar lighter and umbrella holder.”

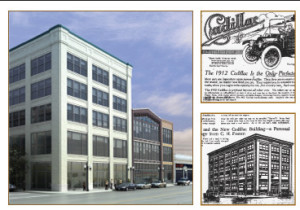

Very quickly, the modest salesrooms were replaced by multistory, terra-cotta temples mimicking the wildly popular Loop movie palaces, their fluted columns and capitals reminiscent of ancient empires. The Spanish Revival Hudson showroom at 2222 S. Michigan shared equal opulence with the adjoining Marmon dealership, both designed by Alfred Alshuler, known for the London Guarantee Building (now Crain Communications) at Wacker Drive and Michigan.

In 1936, Motor Row’s last spectacle, the Spanish Mission-style, Philip Maher designed Illinois Automobile Club opened with an extravagant brochure promising, the Tribune said, “life membership” and “a 21 story clubhouse complete with swimming pool, dance halls and athletic facilities.” Only the foundation and a partial swimming pool were finished, to be later used by the Chicago Defender for its presses. That year, one of the worst in the Great Depression, the entire district, drowning in debt and running on empty, neared collapse.

Feeling the full impact of the Depression, Stutz, Pierce-Arrow, Auburn-Cord, Marmon, Packard and other luxury brands either left or folded. Most of the others followed, hastened by a neighborhood already in decline. The elite had already abandoned Prairie Avenue for Astor Street, and dealers now featured larger indoor showrooms with big outdoor lots closer to customers on Ashland, Western and Cicero avenues and at other city and suburban locations. Finally, World War II stopped civilian car production, ending Motor Row’s long prominence.

The cars and the customers of America’s most intact early auto sales district are gone, but not the vestiges of their young industry. The medallions above the wide windows still show Pierce, Peerless, Buick, Hudson, Locomobile and Marmon. From Roosevelt to Cermak roads, dozens of boarded-up-buildings line Michigan in the landmark district, silent testimony to long-forgotten car brands and the hulking vehicles that braved Chicago’s rutted roads a century ago.

As for Ford’s showroom – an investment made with only $243 remaining in his bank account – the repurposed original building still stands at 1444 S. Michigan as witness to Motor Row’s past and future.

O’Connor’s 1978 Tribune Sunday Magazine feature revealed the Churchill Cabinet War Rooms in London. In 2001 he was named the U.S. Naval Institute “Author of the Year.”

![20130123_140047_resized_001[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/20130123_140047_resized_0011.jpg)

![DSCN6051_000[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/DSCN6051_0001-300x275.jpg)

![FORDORIGINALSHOWROOM[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/FORDORIGINALSHOWROOM1-300x208.jpg)

![coliseum_postcard[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/coliseum_postcard1-300x189.jpg)

![FIRSTREGIMENTALARMORYMI16TH[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/FIRSTREGIMENTALARMORYMI16TH1-300x191.jpg)

![Glessnervintage_001[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Glessnervintage_0011.jpg)

![MOTORROW3014[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/MOTORROW30141-300x225.jpg)

![MOTORROW3016[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/MOTORROW30161-300x225.jpg)

![MOTORROW3011[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/MOTORROW30111-300x225.jpg)