LED BY DODGE-CHICAGO AND ITS B-29 ENGINE PRODUCTION

CHICAGO INDUSTRIES POWERED THE WAY TO VICTORY IN WORLD WAR TWO

When told about the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill envisioned what would come; “Now at this moment I knew that the United States was in the war,up to the neck and in to the death. So we have won after all !” Britain’s wartime leader knew that America’s immense manufacturing potential would lead the world to salvation. The sleeping giant had awakened.

So began one of the most remarkable mobilizations in history as thousands of businesses converted from peace to war manufacturing. Huge new factories were built in months; tens of thousands of workers were recruited, hired and trained even as hundreds of homes were built to house them. And that was just in the Chicago area. Chicago’s large labor pool, expansive rail network and central location – insulated from the threat of enemy bombers – made it an ideal location for such war production.

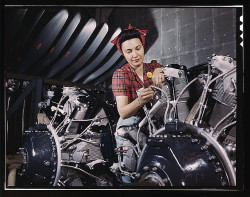

The War Production Board, a federal agency with broad powers, ordered hundreds of Chicago manufacturers to immediately convert, expand, devise and improvise. That led to sometimes jarring changeovers. Radio Flyer ended production of its famous little red wagon at the Grand Avenue factory and switched to blitz cans or fuel containers. Cracker Jack changed to powdered coffee and other GI rations. Chicago Roller Skate Co. retooled to make parts for shells and guns. A manufacturing marathon began at more that 1,400 Chicago-area factories, putting muscle and brains behind nearly every aspect of the war effort, and for the first time hiring thousands of women, sometimes more than 50 percent of a plant’s workforce.

G.D Searle, Baxter and Abbott Laboratories collaborated to mass produce penicillin, the war’s wonder drug. Scores of companies, including Galvin Manufacturing (the precursor to Motorola), Hallicrafters and Webcor, made half of the war’s electronic equipment. In Forest Park, about 10,000 Amertorp technicians assembled 5,000 complex parts for 19,000 torpedoes. The region’s steel mills, including Inland Steel and Republic Steel churned out millions of tons of steel for armor plating. But possibly the most impressive feat, after the creation nearly from scratch of an entire industry, was the production of engines and aircraft at four massive Chicago plants. All told, the region’s industrial might was critical to the Allied victory.

From a million – square foot plant at Archer and Cicero avenues near what was then called Chicago Municipal Airport, Studebaker assembled parts for the B-17 Wright Cyclone engine. Buick’s 125 – acre factory on North Avenue in Melrose Park made nearly 75,000 Pratt & Whitney engines for the B-24 Liberator bomber. In the prairies of unincorporated Cook County at Orchard Place (the source of O’Hare International Airport’s ORD designator), Douglas Aircraft assembled 655 C-54 transport planes in a 2 million- square foot plant – the largest timber building ever made. But it was the 6.3 million-square foot, 19-building, Dodge -Chicago works – “the largest airplane engine factory in the world” – and its B-29 engine production that led all Chicago war production.

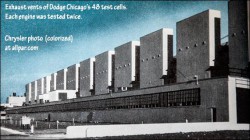

On December 15, 1944, the Tribune noted the shipment to Boeing of the 5,000th Dodge-Chicago B-29 engine: “The plant was turning out at least 90 percent of the engines for the Super Fortress.” Even that record, achieved in only 11 months, was shattered three months later on March 24, 1945, when another 5,000 engines had been completed. “The big job now is for the 32,000 employees at the plant, of whom more than 99 percent are Chicago people, to maintain the peak rate of production,” declated a Chrysler executive, adding that only a little more than 2 1/2 years before the Didge-Chicago plant was only a set of blueprints.

The $458 million facility extended from 71 to 77th Street and from Cicero to Pulaski Road. Inside the 82-acre assembly building, base metals from foundries and forges emerged as fully tested, 18-cylinder, 2,200 horsepower radial engines with 6,000 precision parts, then shipped by rail to a Boeing, Bell, or Martin final assembly plant.

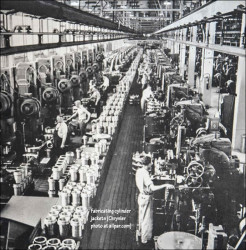

Classroom instruction at the site converted unskilled workers into precision crafters to operate 9,300 metal fabrication machines. Fifteen cafeterias fed 35,000 daily, while seven massive coal-fired boilers produced enough energy for a city of 300,000. By the war’s end, the Dodge-Chicago plant had turned out more than 18,000 engines, nearly five engines for every four-engine B-29 that ever flew.

These massive new factories transformed the neighboring areas. Thousands of workers and their families settled near the plants, buying hundreds of hastily built “war homes” that sold for $6,000 or less or rented for $40-$50 per month. Large tracts took shape across a wide area, especially from Des Plaines south to Melrose Park, Bellwood, La Grange, Westchester, Western Springs, Forest Park and Summitt. Chrysler Village was built for and named after the Dodge plant, which also spurred growth in the sparsley populated area near the fututre Midway Airport. The neighborhoods would become closely knit as most of the residents, men and women, worked the same nine-hour days and six-day weeks. In Park Ridge, scores of two-story Georgian-style homes were built to house officers training to fly the C-54 transports being assembled in the Douglas plant.

The war effort also transformed the workplace by bringing thousands of women onto factory floors and assembly lines. Recognizing the magnitude of that change, the Tribune started a new regular feature in January 1942 called “Women in War Work,” which chronicled the momentous change in the American workplace. But as quick as the mobilization was, the end may have been quicker as the factories closed or returned to civilian use, with the Dodge-Chicago works becoming the city’s biggest white elephant. In 1947, as Dodge-Chicago echoed with abandonment, automobile innovator Preston Tucker leased half of the assembly building for production of his futuristic ‘Tucker 48,’ but manufacturing setbacks, dealer lawsuits, and government prosecution never got the torpedo shaped auto out of first gear. The factory closed after making only 51 cars. Given new life during the Korean War and using much of the same equipment that made the B-29 engines, Ford Motor Co. produced piston and jet engines for the military until 1959 when the factory again closed. What would become Ford City began in 1961 when developer Harry Chadwick bought the entire property and opened the shopping mall in 1965.

Frank Werner began working at Ford City as a Bogan High School sophomore in 1972, and as the shopping center’s chief engineer 41 years later is also custodian of its wartime fame as Dodge-Chicago. “The same tunnels that connected parts of the building are used every day as passageways for shoppers and by Carson-Pirie-Scott for part of its retail store. Even the electrical vaults, switch gear, 12,000 volt cables and transformers are original. In case of an air raid, the 18 inch thick concrete roof was given a mesh interlayer to prevent up to 1,000 pound bombs from exploding on the production floor.”

A curious coda links the wartime Dodge-Chicago saga to the present. In 1967, famously secretive Tootsie Roll Industries began production in a 2 million square-foot section of the former assembly building. Decades later, surrounded by the same concrete exhaust stacks that once tested the mighty engines, the candy factory has an unexpected exhibit alongside confectionery samples given to rare visitors – a fully assembled B-29 engine made in the same building. The Wright Cyclone engine once powered “FIFI,” the last operational B-29 of 3,970 of the legendary bombers made for the single purpose of bringing the war directly to Japan. In 2011, “FIFI” flew dozens of awed visitors on demonstration flights at the DuPage County Air Show.

There was every hope these huge new aircraft enterprises would become permanent industries in Chicago. On January 4, 1943, the Tribune reported: “Well-informed Chicagoans predict that this city at last is well on its way to becoming the nations’s aviation manufacturing center.” While that prediction proved untrue, it is hard to argue that Chicago wasn’t the heart of America’s Arsenal of Democracy.

PHOTO GALLERY: INSIDE AND OUT – THE SAME WAR PLANTS THEN AND NOW

Lane Tech High School during WW II raised War Bond $ to underwrite the cost of a B-17 A Bomber Named The LANE TECH of CHICAGO. B-17G 42-39856. Many people have tried to learn the history of the plane but didn’t get much. I do know much of its history but would like to know is, if the plane was in Chicago for the Christening on Oct. 17 1943. The school has a picture of a plane that is NOT THE LANE TECH of CHICAGO. I know its War history (or most of it) 8th AF 96BG 337BS Snetterton Heath England.

Tom Kane lionelloco@hotmail.com

815 675 6494 Please leave a message

Thanks for your thoughts on the fate of the Lane Tech B17. It is unlikely that the aircraft was in Chicago for its christening. You may be interested in “Mission,” describing the heroic acts of (Col) Jimmy Stewart and his hazardous missions in B-24’s over occupied Europe and Nazi Germany. All of the “Mighty Eighth” bases in East Anglia (about 71) can be located on-line. This may help in your search. Also, read my “Inside the U-boat Pens” on this site. It was awarded “Author of the Year” by the U.S Naval Institute. The Eighth Air Force had the highest casualty rate – about 30,000 men- in the U.S. armed forces in the war. Almost 4,000 are in the American cemetery outside Cambridge, England.