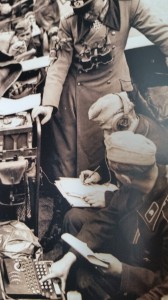

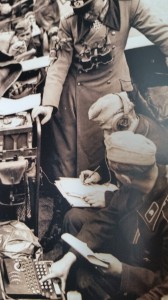

ULTRA – THE SECRET OF THE CENTURY Along with the Manhattan Project, STATION X or Bletchley Park and its war-winning breaking of the ENIGMA cypher machine (shown here with a front-line German signals unit) were the major secrets of World War Two. In preparation for the 1997 feature, the first to be written about Bletchley and it war-winning secret, I visited and photographed the the lonely “huts” and the hulking mansion. I was in the presence of history and felt it deeply, but for most of the day I was also the only visitor. It was little-known then, but fast forward to the present day and witness its conversion into one of the world’s most unique indoor and outdoor museums.

Churchill delightedly referred to the war-winning secret and the thousands who never  revealed it as “the golden geese that never cackled,” but today the place where it happened is as easy to see as taking a fast train from London’s Euston Station, and a short walk to the front entrance. History awaits. Like a many-chambered nautilus, the stark “huts” extending from the mansion took on a different appearance and function as the war progressed and the skills of the code-breakers improved. There they stand in hasty variety, scattered over 50 acres, finished in pine and peeling paint or raw brick, some with portions of unfinished bomb blast walls, and, until recent years, all were hollow with abandonment.

revealed it as “the golden geese that never cackled,” but today the place where it happened is as easy to see as taking a fast train from London’s Euston Station, and a short walk to the front entrance. History awaits. Like a many-chambered nautilus, the stark “huts” extending from the mansion took on a different appearance and function as the war progressed and the skills of the code-breakers improved. There they stand in hasty variety, scattered over 50 acres, finished in pine and peeling paint or raw brick, some with portions of unfinished bomb blast walls, and, until recent years, all were hollow with abandonment.

The odd-bodies and boffins summoned to BP were a curious lot even by the casual standards of the time. Tweedy dons came from Oxford and Cambridge, with droll linguists and pedagogues from newspapers, publishing houses, museums, and rare book stores, with crossword puzzle experts, chess masters and philosophers completing the eccentric aggregation. The unorthodox ensemble was needed because secret messages no longer were produced by humans using words – as in World War 1 – but by machines generating an ever-changing confusion of letter combinations.

The odd-bodies and boffins summoned to BP were a curious lot even by the casual standards of the time. Tweedy dons came from Oxford and Cambridge, with droll linguists and pedagogues from newspapers, publishing houses, museums, and rare book stores, with crossword puzzle experts, chess masters and philosophers completing the eccentric aggregation. The unorthodox ensemble was needed because secret messages no longer were produced by humans using words – as in World War 1 – but by machines generating an ever-changing confusion of letter combinations.

The standard three-rotor Enigma shown here with two spare rotors, messages sent in Morse code into unintelligible cipher text. The mystery to solve was not what went into the machine but how to get the message out, and to do it while there was time to change the outcome of a battle or shift the course of a convoy. The three-rotor Enigma could encipher 159,000,000,000,000,000,000 possible combinations. But in 1942 the Germans introduced even more elaborate machines with up to 12 wheels, including the M4, that locked-out the BP codebreakers for ten desperate months as the Battle of the Atlantic raged on and under the sea.

The standard three-rotor Enigma shown here with two spare rotors, messages sent in Morse code into unintelligible cipher text. The mystery to solve was not what went into the machine but how to get the message out, and to do it while there was time to change the outcome of a battle or shift the course of a convoy. The three-rotor Enigma could encipher 159,000,000,000,000,000,000 possible combinations. But in 1942 the Germans introduced even more elaborate machines with up to 12 wheels, including the M4, that locked-out the BP codebreakers for ten desperate months as the Battle of the Atlantic raged on and under the sea.

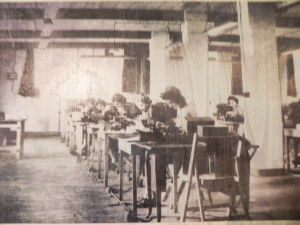

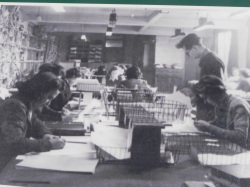

As part of an intricate process, the names of people, places, battles, units, enemy radio stations, even cover names, were  punched into data processing machines that sorted, collated, and cross-referenced the cards into a mammoth index. The punched cards were then stored in constantly expanding one-story buildings in Block C. The mostly women clerks searched up to two million cards weekly to winkle-out the smallest detail to help the codebreakers in the other huts.

punched into data processing machines that sorted, collated, and cross-referenced the cards into a mammoth index. The punched cards were then stored in constantly expanding one-story buildings in Block C. The mostly women clerks searched up to two million cards weekly to winkle-out the smallest detail to help the codebreakers in the other huts.

During my 1998 visit to view a collection of buildings with few  exhibits and even fewer visitors, one’s imagination needed expansion to envision what took place then compared to today’s still evolving information age.

exhibits and even fewer visitors, one’s imagination needed expansion to envision what took place then compared to today’s still evolving information age.

Between then and now an amazing transformation has taken place. Where there was emptiness in 1996 there is now major activity. On the day of my 2015 return visit, twelve fully loaded motor coaches plus hundreds more visitors who came by rail or auto now visited what was once the most secret place in war torn Europe. Compare the original photo above with the same room now.

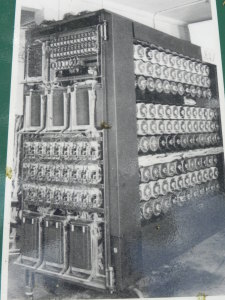

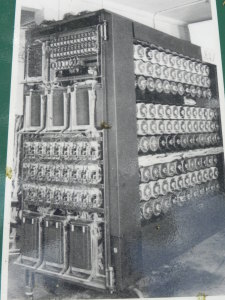

As early as January 1940, only 5 months after the war’s start, BP codebreakers already had entered Enigma’s labyrinth. They were aided by the curiously named “bombe” (below) an electro-mechanical machine that could be plugged with clues or “cribs” to produce menus for possible solutions or “break-in’s.” It was intended to mimic the same

way that an Enigma may have been set by its operator. With number and letter instructions gained from results from the hot and noisy sprocket driven machines, one or more of the “bombes” would clatter to a stop, followed by the report of “jobs up,” meaning that Enigma had been penetrated again. An unexpected intelligence coup saved months of labor when Polish mathematicians gave the British plans for the “bombe,” and the Polish secret service gave the British an actual working Enigma. With thousands of solutions from the Enigma riddle during the war and with over 12,000 on the staff, only four persons had full details of the secret.

way that an Enigma may have been set by its operator. With number and letter instructions gained from results from the hot and noisy sprocket driven machines, one or more of the “bombes” would clatter to a stop, followed by the report of “jobs up,” meaning that Enigma had been penetrated again. An unexpected intelligence coup saved months of labor when Polish mathematicians gave the British plans for the “bombe,” and the Polish secret service gave the British an actual working Enigma. With thousands of solutions from the Enigma riddle during the war and with over 12,000 on the staff, only four persons had full details of the secret.

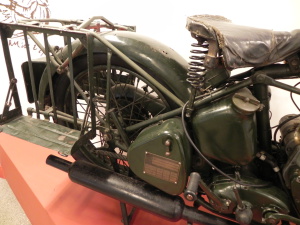

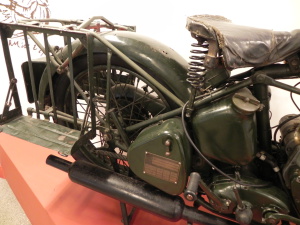

Farther afield, thousands of radio operators at coastal intercept stations, supplied masses of raw, encrypted Enigma messages that often originated under appalling conditions. Enemy transmissions alternated among 226 radio frequencies, with Enigma messages averaging only 10 seconds in duration. Successful detection had to overcome constant frequency changes, enemy jamming, static, howling whistles and squeals, and the ordinary sounds of music or dialogue. Once intercepted at the ‘Y’ or coastal listening stations, raw messages were packed into the side compartments of motorcycles, including this one, and delivered – up to 50 per hour – to BP for potential solution. Later in the war secure teleprinters greatly improved the process from intercept to analysis. Choice intercepts were sent to Churchill in his own secret complex at the Cabinet War Rooms in central London. (Jerome O’Connor was the first to reveal the existence of the mythic war rooms. The original Chicago Tribune feature is elsewhere on this site.)

Farther afield, thousands of radio operators at coastal intercept stations, supplied masses of raw, encrypted Enigma messages that often originated under appalling conditions. Enemy transmissions alternated among 226 radio frequencies, with Enigma messages averaging only 10 seconds in duration. Successful detection had to overcome constant frequency changes, enemy jamming, static, howling whistles and squeals, and the ordinary sounds of music or dialogue. Once intercepted at the ‘Y’ or coastal listening stations, raw messages were packed into the side compartments of motorcycles, including this one, and delivered – up to 50 per hour – to BP for potential solution. Later in the war secure teleprinters greatly improved the process from intercept to analysis. Choice intercepts were sent to Churchill in his own secret complex at the Cabinet War Rooms in central London. (Jerome O’Connor was the first to reveal the existence of the mythic war rooms. The original Chicago Tribune feature is elsewhere on this site.)

The joint military and civilian staff worked on trestle tables set up in drafty, poorly lighted,and hastily constructed temporary buildings extending from the mansion, with women outnumbering men eight to one. The military wore uniforms without badges of rank or unit markings. Civilians dressed in tweed or corduroy, and everyone worked furiously, eight hours on and eight hours off around the clock. From the day the war started until the day it ended six years later, the pace continued unabated.

Still little-known is the presence in Block D of 230 American cryptanalysts. This block was so privileged – a secret within a secret – that its 1,000 member staff was itself separated by individual departments, none knowing what the others were doing on the other side of separating walls in the same building.

There was good reason for the added security deep within what was already the most secure place in Britain. Within Block D a traffic analysis section known as SIXTA assembled individual puzzle pieces from scores of thousands of Enigma intercepts. The history-changing result disclosed the German order of battle and the location of every unit and vessel. It contributed to a vast deception with the Nazi’s believing that the June 6, 1944 invasion would happen in the Pas de Calais instead of Normandy. Churchill gave top priority to Bletchley’s revelations and shared the results with his friend and savior, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

There was good reason for the added security deep within what was already the most secure place in Britain. Within Block D a traffic analysis section known as SIXTA assembled individual puzzle pieces from scores of thousands of Enigma intercepts. The history-changing result disclosed the German order of battle and the location of every unit and vessel. It contributed to a vast deception with the Nazi’s believing that the June 6, 1944 invasion would happen in the Pas de Calais instead of Normandy. Churchill gave top priority to Bletchley’s revelations and shared the results with his friend and savior, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

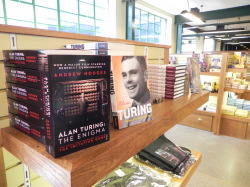

ALAN TURING – THE ENIGMA The inaccuracies in the film The Imitation Game aside, the history-changing accomplishments of the Bletchley Park codebreakers were now fully revealed to a world audience. The genius who was a major figure in the breaking of Enigma was at home in his world of figures and computations, but seldom elsewhere. Peculiar practices clung to Turing like layers of moor fog. To his BP colleagues he was “the Prof,” often seen distractedly hurrying to or from the mansion and Hut 8, the section struggling to break the U-Boat code. To his neighbors in nearby Shenley Village, he was the odd one on the bicycle wearing a gas mask, the best thing for relief of chronic allergies, he believed. He was iconoclastic, contradictory, and eminently mysterious, the perfect ingredients for an eccentric scientist, or for a demented uncle locked in the attic. His mind was occupied with constant calculation. In determining that a loose bicycle chain would come off after 14 turns, he would stop to adjust the chain after each 13 revolutions. But he also knew that this habit was also part of the chain of inferences necessary for breaking Enigma. The inferences led to either a contradiction (you were wrong and moved to the next position on the rotor) or a confirmation as the likely letters were transformed into words and then a solution. Scientists then and now use the same approach to determine the probability of any assumption: observe and conclude. The Bletchley gift store recognizes Turing’s fame with various books, and with his Hut 8 office open to view nearby.

ALAN TURING – THE ENIGMA The inaccuracies in the film The Imitation Game aside, the history-changing accomplishments of the Bletchley Park codebreakers were now fully revealed to a world audience. The genius who was a major figure in the breaking of Enigma was at home in his world of figures and computations, but seldom elsewhere. Peculiar practices clung to Turing like layers of moor fog. To his BP colleagues he was “the Prof,” often seen distractedly hurrying to or from the mansion and Hut 8, the section struggling to break the U-Boat code. To his neighbors in nearby Shenley Village, he was the odd one on the bicycle wearing a gas mask, the best thing for relief of chronic allergies, he believed. He was iconoclastic, contradictory, and eminently mysterious, the perfect ingredients for an eccentric scientist, or for a demented uncle locked in the attic. His mind was occupied with constant calculation. In determining that a loose bicycle chain would come off after 14 turns, he would stop to adjust the chain after each 13 revolutions. But he also knew that this habit was also part of the chain of inferences necessary for breaking Enigma. The inferences led to either a contradiction (you were wrong and moved to the next position on the rotor) or a confirmation as the likely letters were transformed into words and then a solution. Scientists then and now use the same approach to determine the probability of any assumption: observe and conclude. The Bletchley gift store recognizes Turing’s fame with various books, and with his Hut 8 office open to view nearby.

THE “MAIN HOUSE” – WHERE IT ALL BEGAN

The 1870s mansion, known as the Main House, was the headquarters and center of the entire operation. Shown below is a rare wartime photo and the same view today. Until April 1942, when a separate building served as the staff canteen, the main dining room below served as the cafeteria, and then became the dining room for senior staff. The Main House continuously served as offices for the senior staff, with the former billiard room converted into a telephone exchange, later to be moved into its separate blast proof hut. The telephone exchange switchboard facilitated communication later in the war from teleprinters then installed in the ‘Y’ or coastal listening stations. The teleprinters largely replaced the delivery of messages by motorcycle.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

After VJ Day and the end of the second great war of the century, the codebreakers went back to their lives secure in the knowledge that they had helped save civilization. What part of it they had saved they didn’t know, not until their first reunion in 1996 at, of course, Bletchley Park.

As required by the Official Secrets Act until its 1972 expiration and which everyone signed, all who served at Bletchley were obliged to never disclose the secret of the century. Its violation in wartime could have resulted in death. But the “golden geese never cackled” and the secret was never revealed.

The epic achievement of the BP codebreakers will be remembered as one of history’s greatest accomplishments in war or peace. As the direct result of the breaking of Enigma and the later solution to the Nazi’s “secret writer” machine, many thousands of Allied and enemy lives were spared. Battles were won or avoided; wolf-pack lanes skirted or attacked. Top Secret Ultra knew enemy intentions often before they were communicated to the field. Ultra revealed orders of battle, situation reports, details of fuel and ammunition reserves, manpower shortages, spare parts inventories; indeed, the state of readiness of every unit in the armed forces. Ultra knew the exact number of men, aircraft and tanks committed to a battle. What the Germans did not know about Allied strategy was as vital as what Ultra DID know about enemy plans.

D-Day took place in 1944 instead of 1945 because Ultra knew that the Germans were confused about the actual landing area and that 19 German divisions were waiting for an attack from the nonexistent army of Gen. George Patton to a never-intended landing area, the Pas de Calais. Ultra helped win the Battle of the Atlantic, the crucial battle of El Alamein, and contributed to the American breaking of Japanese codes that helped win the Battle of Midway.

America’s major accomplishment in breaking the Japanese diplomatic “Purple” cypher began well before the attack at Pearl Harbor, was also known by only a few and called by its own code, “Magic.” However, the content within Purple was unable to provide sufficient detail to know the precise location of the December 7, 1941 attack, only the likelihood of an attack somewhere in the Pacific. Shortly after Pearl Harbor the Japanese naval code was also broken, which produced the battle-winning clues leading to the decisive victory at the Battle of Midway. The U.S. Navy’s decisive victory at Midway permanently stopped the Japanese advance across the Pacific. Because of a finally awakened United States citizenry, everything before Midway was loss, but all that followed was victory.

The greatest of America’s late 19th and early 20th century architects were unafraid to take risks, to become adventurers and boldly explore all that the science and technology of the era would allow. Also consider Frank Lloyd Wright’s little known Florida Southern College campus (L). By disregarding the comfort of endlessly repeating classical styles, they embraced an uncertain future, but they also knew that America as a new nation also needed to express its own architecture, just as did earlier civilizations.

The greatest of America’s late 19th and early 20th century architects were unafraid to take risks, to become adventurers and boldly explore all that the science and technology of the era would allow. Also consider Frank Lloyd Wright’s little known Florida Southern College campus (L). By disregarding the comfort of endlessly repeating classical styles, they embraced an uncertain future, but they also knew that America as a new nation also needed to express its own architecture, just as did earlier civilizations.

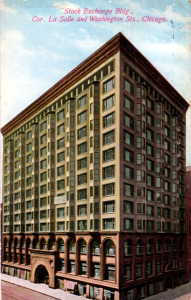

century architecture. Thus, they were also pioneers, never fully certain where the new direction would take them, their clients, or the environment they designed. In creating the new movement, to be called the Chicago School of Architecture, the early architects became adventurers, of whom none had more influence on the future than Louis Henri Sullivan. (L & above)1893 Chicago Stock Exchange and 1899-1904 Carson Pirie Scott).

century architecture. Thus, they were also pioneers, never fully certain where the new direction would take them, their clients, or the environment they designed. In creating the new movement, to be called the Chicago School of Architecture, the early architects became adventurers, of whom none had more influence on the future than Louis Henri Sullivan. (L & above)1893 Chicago Stock Exchange and 1899-1904 Carson Pirie Scott).

The odd-bodies and boffins summoned to BP were a curious lot even by the casual standards of the time. Tweedy dons came from Oxford and Cambridge, with droll linguists and pedagogues from newspapers, publishing houses, museums, and rare book stores, with crossword puzzle experts, chess masters and philosophers completing the eccentric aggregation. The unorthodox ensemble was needed because secret messages no longer were produced by humans using words – as in World War 1 – but by machines generating an ever-changing confusion of letter combinations.

The odd-bodies and boffins summoned to BP were a curious lot even by the casual standards of the time. Tweedy dons came from Oxford and Cambridge, with droll linguists and pedagogues from newspapers, publishing houses, museums, and rare book stores, with crossword puzzle experts, chess masters and philosophers completing the eccentric aggregation. The unorthodox ensemble was needed because secret messages no longer were produced by humans using words – as in World War 1 – but by machines generating an ever-changing confusion of letter combinations.