UNVEILING THE CHURCHILL WAR ROOMS

“ LONDON BLASTED ANEW FROM AIR” “…Attacks were most violent in all the five previous weeks of the aerial siege of Britain’s capital…400 killed… Waterloo Station, St. Paul’s Cathedral hit.” (Headline: Frederick, MD POST) On that day in 1940 the forward movement of democracy and civilization seemed to pause. The Nazi invasion of the British Isles was expected by spring 1941 at the latest, and America’s ambassador to Great Britain, Joseph P. Kennedy, no supporter of England ’s chances, was summoned to Washington for urgent talks. The lights in the White House burned brightly all night, as President Franklin D. Roosevelt readied a seven-minute radio address to the American people. It would announce a compulsory peacetime draft of 16 million men. That day, fourteen months before Pearl Harbor, America readied for war.

TUESDAY 15 OCTOBER 1940, LONDON, ENGLAND

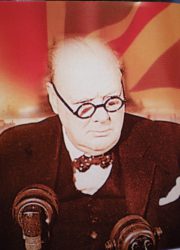

At 5 feet six inches, Winston S. Churchill possessed a resolute bearing that denied his height. Boarding his limousine for the brief trip from Number 10 Downing Street, he had an especially vital task that day. London’s port facilities were in ruins from almost daily air attacks, and needed immediate repair. Nine hundred fires raged out of control. The heaviest air raid to date thundered overhead. Five months earlier, May 10 1940, the day he became Prime Minister, Germany invaded the Low Countries. Two weeks later, 338,000 Tommies and other troops evacuated Dunkirk in defeat. Six British and three French destroyers were sunk. All of the army’s heavy equipment and vehicles remained on the beach. Only the English Channel lay between the Nazi hordes and victory. The battle of France began that first day in office, only to end in a humiliating French surrender a mere six weeks later. Now, five months on, Churchill knew well that Britain’s fate hovered over a vast chasm, with the near certainty of apocalyptic destruction rained from above over the storied kingdom by the sea. Perhaps Ambassador Kennedy was correct in saying that England’s prospects were “hopeless.”

As he entered the underground concrete compound, two bodyguards following, a Romeo and Julieta cigar haze trailing, a Royal Marine came to attention on a coconut and rubber floor mat. Whistling, loud talk, and hall gatherings stopped. The PM was acutely sensitive to any sound – except the sound of his own voice. He entered the hastily built Cabinet War Rooms, an enclave more resembling a basement – which it was – than the stronghold there was no time to build. Churchill’s war headquarters resided a mere ten feet below the 1906 built Ministry of Work’s ground floor. As conspicuous as a jack-o-lantern in a snow bank, the squat, sooty government building hid in plain sight. The labyrinth of rooms on which Britain’s future depended, stood directly across from St. James Park, an easy target for German paratroopers, and a two minute walk through a connecting tunnel from Downing Street to the Cabinet War Rooms. The previous night, a bomb hit Number 10, killing three people. Only a single Royal Marine guarded the entry known as Number One Storey’s Gate, and he was concealed behind the double-door exterior entrance. Only a three foot exterior concrete blast wall hinted at something unusual occurring inside. At precisely 5pm Churchill went into the relatively spacious Cabinet Room, his ministers smoking and whispering among themselves, prepared to discuss red-flagged briefing papers in manila folders. “Gentlemen, let us begin.”

Taking his seat at a wooden chair in front of a five by ten foot Rand McNally world map, the King’s red wooden dispatch box on the table before him, Churchill knew that of all the current and coming crises England confronted, the circumstances at sea were especially appalling. Anticipating action, on September 1, 1939, the day war started, eleven U-boats were already at sea. Two days later on the day war was declared, U30 sank the passenger liner Athenia, signaling the start of unrestricted submarine warfare. By the end of the war’s first month, U-boats had already sunk 63 merchant ships, losing only five in return, an exchange Britain could not long sustain. When the war began, Britain had 6,700 merchant steamers, the largest such fleet in the world, and more than twice that of her nearest competitor, the United States. But, as an island empire, Great Britain’s dependence on peacetime imports proved to be her greatest weakness in wartime. Only one month after the first minister’s meeting in the war rooms, coordinated wolf-packs sank thirty-four merchant ships in only 48 hours. In the early years of the war, 280,000 tons of Allied shipping went to the bottom each month. In memoirs after the war, Churchill wrote that, “…the U-boats were the only fear I had in the entire war.”

Taking his seat at a wooden chair in front of a five by ten foot Rand McNally world map, the King’s red wooden dispatch box on the table before him, Churchill knew that of all the current and coming crises England confronted, the circumstances at sea were especially appalling. Anticipating action, on September 1, 1939, the day war started, eleven U-boats were already at sea. Two days later on the day war was declared, U30 sank the passenger liner Athenia, signaling the start of unrestricted submarine warfare. By the end of the war’s first month, U-boats had already sunk 63 merchant ships, losing only five in return, an exchange Britain could not long sustain. When the war began, Britain had 6,700 merchant steamers, the largest such fleet in the world, and more than twice that of her nearest competitor, the United States. But, as an island empire, Great Britain’s dependence on peacetime imports proved to be her greatest weakness in wartime. Only one month after the first minister’s meeting in the war rooms, coordinated wolf-packs sank thirty-four merchant ships in only 48 hours. In the early years of the war, 280,000 tons of Allied shipping went to the bottom each month. In memoirs after the war, Churchill wrote that, “…the U-boats were the only fear I had in the entire war.”

Returning for rest and overhaul to their five impregnable bases along France’s Bay of Biscay, the wolf-packs were soon back at sea, proving they were the hunters, and the thin convoy fibers originating from the United States and Canada were the hunted. Churchill had to buy time before regaining mastery of the seas. But there was neither money nor time. England ’s only hope lay with the 32nd President of the United States, his great and good friend, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Returning for rest and overhaul to their five impregnable bases along France’s Bay of Biscay, the wolf-packs were soon back at sea, proving they were the hunters, and the thin convoy fibers originating from the United States and Canada were the hunted. Churchill had to buy time before regaining mastery of the seas. But there was neither money nor time. England ’s only hope lay with the 32nd President of the United States, his great and good friend, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

On February 9, 1941, transmitted by BBC short wave, Churchill addressed these words directly to America : “The other day President Roosevelt gave his opponent… a letter of introduction to me. And in it he wrote out a verse in his own handwriting from Longfellow…here is the verse: ‘Sail on oh ship of state, sail on oh Union strong and great. Humanity with all its fears, with all the hopes of future years, is hanging breathless on thy fate.’ What is the answer that I shall give in your name to this great man? Here is the answer that I will give to President Roosevelt: Put your confidence in us. Give us your faith and your blessing, and under Providence all will be well. We shall not fail or falter; we shall not weaken or tire. Neither the sudden shock of battle nor the long drawn trials of vigilance will wear us down. Give us the TOOLS and we will FINISH the job.”

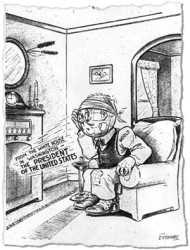

![FDR_FOR_SS_10808[1]](https://historyarticles.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/FDR_FOR_SS_108081.gif) The “Arsenal of Democracy” Dismayed by the results of the 20th Century’s first Great War, its outcome pointing directly to a second, even bloodier conflict, FDR presided over a fractious electorate of 132 million. He had won 38 of 48 states in the 1940 election, but held only a slender 5% plurality. Still in recovery from the Great Depression, in 1940 American unemployment exceeded 14%. Yet, FDR largely succeeded in reassuring the American people with Sunday evening radio “fireside chats,” and an infectious upbeat outlook. But, at the end of the day, how could he help England when Congress had prohibited full rearmament by enacting a series of neutrality acts punishing friend and foe equally? And, lacking naval contracts, America’s shipyards echoed with emptiness. Congress finally gave the Navy a trivial $250 million for new shipbuilding and systems modernization of its mostly obsolete ships. The American military had all but disarmed after 1918, with the US Army fielding thousands more cavalry horses than fully armed mobile divisions. If stressed, the US could muster 6 divisions. but Germany’s globe-dominating military had ten percent (6.8 million) of its population already fully trained and ready for war. In 1940, the US military ranked 18th in the world; even tiny Portugal had more men under arms than America.

The “Arsenal of Democracy” Dismayed by the results of the 20th Century’s first Great War, its outcome pointing directly to a second, even bloodier conflict, FDR presided over a fractious electorate of 132 million. He had won 38 of 48 states in the 1940 election, but held only a slender 5% plurality. Still in recovery from the Great Depression, in 1940 American unemployment exceeded 14%. Yet, FDR largely succeeded in reassuring the American people with Sunday evening radio “fireside chats,” and an infectious upbeat outlook. But, at the end of the day, how could he help England when Congress had prohibited full rearmament by enacting a series of neutrality acts punishing friend and foe equally? And, lacking naval contracts, America’s shipyards echoed with emptiness. Congress finally gave the Navy a trivial $250 million for new shipbuilding and systems modernization of its mostly obsolete ships. The American military had all but disarmed after 1918, with the US Army fielding thousands more cavalry horses than fully armed mobile divisions. If stressed, the US could muster 6 divisions. but Germany’s globe-dominating military had ten percent (6.8 million) of its population already fully trained and ready for war. In 1940, the US military ranked 18th in the world; even tiny Portugal had more men under arms than America.

The United States had no munitions industry, and with Holland ’s surrender came the potential of ending virtually any manufacture of arms requiring rubber. Ninety percent of America’s rubber came from the Netherlands East Indies. Newspaper publishers savaged FDR almost daily. Unsympathetic editorials in 85% of America’s newspapers opposed Roosevelt ’s pleas for re-armament. Gallup polls reported that the majority of Americans supported appeasement. And the powerful isolationist’s lobby had a new champion in America’s hero, Charles Lindbergh. In packed speeches, including the 18,000 seat Chicago Stadium, Lindbergh accused the Roosevelt administration of promoting a “defense hysteria.” Sensing danger, Congress conceded by approving “cash and carry” accords, grudgingly sending the Royal Navy 50 WW1 destroyers. Churchill had been informed that rescue from America by sea was only a matter of months away – if England could survive that long. Liberty ships, the war’s “ugly ducklings,” eventually would number 2,751 vessels built on average in only 42 days at 18 U.S. shipyards. The past failures and likely future setbacks on land and at sea, tugged at Churchill’s thoughts before that first meeting on October 15, 1940. He needed America and he needed her now, or England would lose the war. It was that certain.

The Cabinet War Rooms, London Although the current public entrance is not the original wartime entry, CWR staffers returning for a nostalgic visit decades later would not be disappointed. The rooms are as complete in appearance and appointments as they were then. The entire headquarters staff seems to have departed for a celebratory pint on VJ Day,15 August 1945, but never returned.The same places are set in the Cabinet Room as when Churchill opened the first meeting in 1940.  Here, the wartime coalition government and separate Defense Committee convened regularly. Meetings, called the “Midnight follies,” could begin at any time of the day or night. A famously late-retiring Churchill might call an evening conference, only to conclude it well after Midnight. On average, 15 ministers and ministers without portfolio attended. At various times they included Neville Chamberlain, Clement Attlee, Sir Hastings Ismay, General Alan Brooke, Viscount Halifax, Anthony Eden, Lord Beaverbrook, and others. Churchill presided from a wooden chair with arm rests at the top of a hollow square of tables covered with blue cloth. The ministers analyzed briefing papers, summaries, maps and charts. An overhead brightly red painted interlace of steel beams glinted over the proceedings.

Here, the wartime coalition government and separate Defense Committee convened regularly. Meetings, called the “Midnight follies,” could begin at any time of the day or night. A famously late-retiring Churchill might call an evening conference, only to conclude it well after Midnight. On average, 15 ministers and ministers without portfolio attended. At various times they included Neville Chamberlain, Clement Attlee, Sir Hastings Ismay, General Alan Brooke, Viscount Halifax, Anthony Eden, Lord Beaverbrook, and others. Churchill presided from a wooden chair with arm rests at the top of a hollow square of tables covered with blue cloth. The ministers analyzed briefing papers, summaries, maps and charts. An overhead brightly red painted interlace of steel beams glinted over the proceedings.

Today, as if ready for a hastily called meeting, the table holds the same ink stained blotters, with pencils and files askew. One tagged file on the table reads OPERATION OVERLORD – TOP SECRET. Hitler would have sacrificed millions more lives for that one file detailing plans for the Allied invasion on June 6, 1944. The separate Map Room is even more complete. A wall to ceiling map showing punctures from thousands of colored push-pins, displays the perilous convoy routes from Hampton Roads to Halifax and on to the British ports. On a raised center console surrounded by desk positions strewn with notes and manila files, seven different colored telephones, dubbed the “beauty chorus” were linked worldwide.

Today, as if ready for a hastily called meeting, the table holds the same ink stained blotters, with pencils and files askew. One tagged file on the table reads OPERATION OVERLORD – TOP SECRET. Hitler would have sacrificed millions more lives for that one file detailing plans for the Allied invasion on June 6, 1944. The separate Map Room is even more complete. A wall to ceiling map showing punctures from thousands of colored push-pins, displays the perilous convoy routes from Hampton Roads to Halifax and on to the British ports. On a raised center console surrounded by desk positions strewn with notes and manila files, seven different colored telephones, dubbed the “beauty chorus” were linked worldwide.

Their insistent ring-ring sent watch officers and messengers scurrying to receive or send messages over the telephones or through pneumatic tubes. Fourteen telephone lines went to British forces, the U.S. military, to embassies, and to the Commander-in-Chief, Western Approaches in Liverpool. Two lines connected to the White House. Frequent calls between Churchill and Roosevelt originating from a separate broom- closet sized room, discussed the latest discoveries from top secret ULTRA. Over 12,000 code-breakers at Bletchley Park, the “golden geese that never cackled,” had already solved the primary means of secret German military communication.

Their insistent ring-ring sent watch officers and messengers scurrying to receive or send messages over the telephones or through pneumatic tubes. Fourteen telephone lines went to British forces, the U.S. military, to embassies, and to the Commander-in-Chief, Western Approaches in Liverpool. Two lines connected to the White House. Frequent calls between Churchill and Roosevelt originating from a separate broom- closet sized room, discussed the latest discoveries from top secret ULTRA. Over 12,000 code-breakers at Bletchley Park, the “golden geese that never cackled,” had already solved the primary means of secret German military communication.

They had deciphered the myriad intricacies of the electro-mechanical Enigma machine. Fifty decrypts a day in 1940, multiplied to 3,000 daily in 1943. The war-winning accomplishment gave the Allies details of Hitler’s schemes, even before his armies knew.

Back in the narrow, windowless, single corridor in the Cabinet War Rooms, a notice board with changeable cards reported on the weather outside, such as “fine,” “rainy,”and “windy.” With typical British stiff upper lip, the “windy” card referred not to the movement of air, but to the presence of air raids above. Nonetheless, the sound of bombs falling within yards of the building was sufficient indication of conditions above.

Midway along the hall, a room with signs above the door states: THE PRIME MINISTER, and SILENCE. This was Churchill’s austere combination bedroom and office, called the “holy of holies” by the ever dutiful staff. Photos, personally selected by Lady Clementine, line the walls. On one side of the room, his desk has a bound copy of “Dod’s Parliamentary Companion,” awaiting his unlikely perusal. From the two BBC desk microphones, Churchill made four speeches rallying the world at war. At the room’s opposite end, his single-sized bed with walnut headboard is routine enough – his folded bedclothes are at the ready – but oversize wall maps verify that this was the headquarters of a leader under siege. A seven by nine foot wall map in the bedroom was almost always concealed by drapes; General Dwight D. Eisenhower was one of few to view it. Here, in the innermost sanctum of the Cabinet War Room’s secret spaces, the map shows the British beaches where the Nazi’s were expected to land. Red and blue circles, and dotted and straight lines, reveal how little of the country was fully defended. For all of Churchill’s boldness in thought and action, even he expected the worst. A separate telephone room has – for the time and place – state of the art switchboards. Six operators were on duty day and night. In another tiny room, a pool of four typists hunched over black Remington’s, and duplicated correspondence on a mimeograph. Another small room contains a full kitchen, lacking only cooks to prepare meals. A range, a double-doored oven, cooking utensils, containers of additives and ingredients, electric oven-top grill, and the essential oversize metal tea kettle, anticipate a hurried Midnight meal request.

Overall, here is a museum that not only portrays a valuable segment of the 20th Century’s most important event, World War Two, but lives and breathes that same history in unsurpassed detail. Even more, the bulldog tenacity of one of history’s transcendent giants is on full display, starting from the day when Winston Churchill first inspected the facility and said: “This is the room from which I will conduct the war.”

Jerome M. O’Connor, Chicago Tribune, October 22, 1978